In an age where glass cockpits, autopilots, GPS systems, and electronically controlled engines dominate general aviation, having a rock-solid electrical system isn’t just a convenience—it’s a necessity. That’s especially true for the Sling TSi, a sleek and modern aircraft that relies on digital avionics and electronic fuel injection to keep everything running smoothly.

Powering the Modern Cockpit: The Rotax 915/916iS Electrical System

At the heart of its electrical system is the Rotax 915 iS/916 iS engine, which comes with a built-in dual alternator setup. But as I dug into the details of how these alternators work, I realized that while they provide a solid baseline of power, there are situations where adding an external alternator makes a lot of sense.

To make an informed decision, I prepared a paper describing the Rotax internal alternator system and evaluating the pros and cons of adding an external alternator.

The rest of this post is a summary of the information included in the paper. A crash course on how the Rotax 915/916iS engine electrical system works can be found in these two excellent YouTube videos.

So, after carefully evaluating the pros and cons, I made our decision: I am adding an external alternator to our Sling TSi. Here’s why.

How the Rotax Alternators Work

The Rotax 915/916 engines come equipped with two built-in alternators that share a single stator but operate independently. Here’s how they’re designed:

- Alternator A (16A, ~220W): Dedicated solely to powering the engine’s electronic control unit (ECU), ignition system, and fuel pumps.

- Alternator B (28A, ~420W): Supplies power to everything else in the aircraft—avionics, displays, lights, radios, and battery charging.

This dual alternator setup ensures that even if one alternator fails, the engine can keep running. Alternator A is always prioritized for engine power, while Alternator B carries the burden of keeping the aircraft’s electrical system running. In normal operation, it works well—but under heavy electrical loads, there are potential limitations.

Why Two Isn’t Always Enough

While the 30A capacity of Alternator B is generally sufficient for most VFR operations, it can get stretched to its limit in IFR conditions or when running multiple high-power accessories. Let’s break it down:

- A typical IFR panel with dual glass screens, an autopilot, and radios could consume 25+ amps (see the Midwest Panel Builders You Tube video for how to calculate).

- If you add pitot heat, landing lights, oxygen concentrator, mobile electronics charging, and other electrical load, you’re at risk of exceeding the available power.

- If Alternator B fails, all avionics immediately fall back to the battery, which has limited endurance—potentially as little as 20–30 minutes.

In short, if Alternator B fails, you could be flying with a rapidly draining battery, scrambling to reduce power consumption. And if you’re flying IFR or at night, that’s not an ideal situation.

Failure Scenarios and Why It Matters

When considering an external alternator, the big question is: how does it help in an emergency? Let’s look at three scenarios:

1. Failure of Alternator A (Engine Alternator)

- The engine automatically switches to Alternator B for power.

- However, Alternator B stops feeding the avionics and the battery stops charging.

- Without an external alternator, the aircraft is now running solely on battery power.

- With an external alternator, avionics and lights can keep running without draining the battery.

2. Failure of Alternator B (Aircraft Alternator)

- The engine keeps running on Alternator A, but the avionics lose their primary power source.

- Again, without an external alternator, avionics rely only on battery power.

- With an external alternator, it takes over, keeping the electrical system fully operational.

3. Dual Alternator Failure (Extremely Rare)

- Without backup power, the engine shuts down once the battery is depleted.

- With an external alternator, it could keep the battery charged, allowing an emergency landing with full avionics and engine operation.

The External Alternator Solution

To mitigate this risk, I am installing a belt-driven external alternator on the Rotax 915 iS. This optional alternator mounts to the front of the engine and provides an additional 40 amps of electrical power. Here’s what that means:

- More than double the available power to run avionics and accessories.

- Redundancy—if Alternator B fails, the external alternator can take over powering avionics and recharging the battery.

- Load balancing—reduces strain on Alternator B, preventing it from constantly running at max capacity.

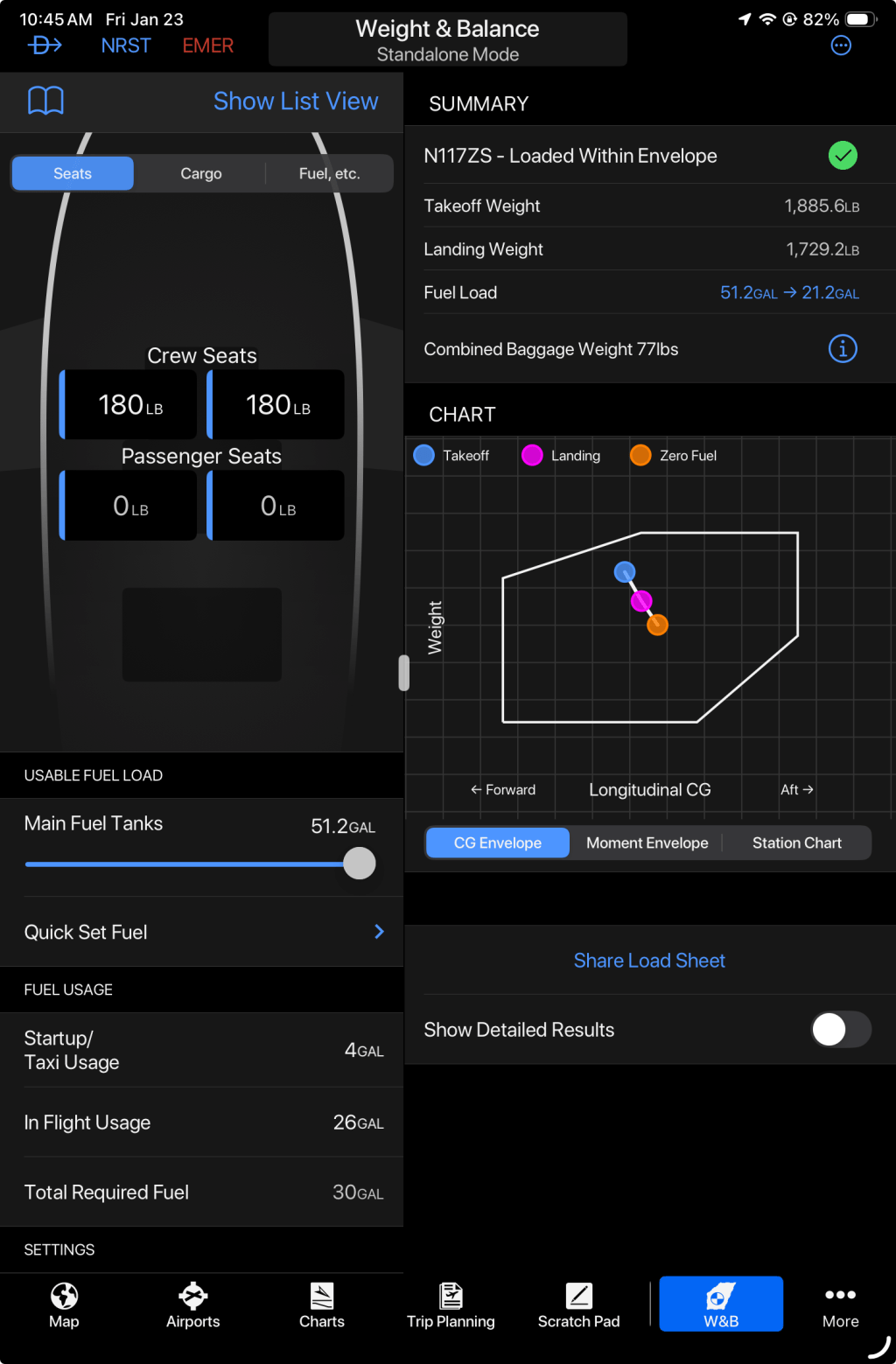

- A small forward weight shift, which helps balance the Sling TSi’s naturally aft-heavy CG when loaded with passengers.

This Midwest Panel Builders video provides a good overview of the way to calculate electrical load and what are the implications in the external generator decision.

The Downsides? Not Many.

Of course, adding an external alternator isn’t without trade-offs:

- It adds about 3 kg (6.6 lbs) to the nose of the aircraft, which actually is partially a pro, as it helps move the CG of the airplane forward.

- There’s a minor power draw from the engine when running the external alternator.

- Installation and wiring add some complexity to the build.

- Cost of approximately $3000.

However, the added safety and redundancy far outweigh these minor drawbacks, particularly for IFR and long-distance flights.

Final Decision: More Power, More Confidence

After weighing the risks, benefits, and failure scenarios, it became clear: the external alternator is a smart addition to our Sling TSi build. It provides additional power, improves redundancy, and ensures that I won’t be left in the dark if an alternator fails. It’s a small investment for a big safety payoff.

Leave a comment