This post walks through how I set up Weight & Balance for a Sling TSi in Garmin Pilot, and how I use that setup to explore realistic scenarios where aft CG can become a consideration, particularly in a parachute-equipped aircraft.

A few important notes up front.

First, Garmin Pilot requires a complete aircraft profile before it will save anything. That means you need to be ready to enter all required data—envelope limits, stations, and aircraft details—in one pass.

Second, all inputs I use in Garmin Pilot are in imperial units (pounds and inches). The Sling POH presents some key data in metric and imperial units, but still so part of the setup involves careful unit conversion. Those conversions are shown explicitly so they can be verified and reused.

Third, the numbers used here for the specific aircraft W&B configuration are not the final numbers for my airplane. At the time of writing, I am using data from a reference Sling TSi with a similar configuration. This allows the Garmin Pilot profile to be built, validated, and used meaningfully now. When my aircraft’s final empty weight and CG are available, only those values will change—the structure of the setup will not.

Fourth, all data in this post is based on the Sling TSi POH (Rev 3.3). If you are working from a different POH revision, you should always defer to your document and adjust accordingly.

Finally, the goal here is validation, not blind data entry. Every envelope point, station, and result should make sense when cross-checked against the POH and against physical intuition. If the software produces a result that doesn’t pass a basic sanity check, the model—not the airplane—needs to be questioned.

With that context set, we’ll start by briefly reviewing the key weight and balance concepts, then walk through the Garmin Pilot configuration step by step, and finally use that setup to examine realistic loading scenarios where aft CG margins can tighten toward the end of a flight.

Weight & Balance Concepts (Quick Refresher)

Before touching Garmin Pilot, it helps to align on a few core weight and balance concepts. These aren’t new ideas, but having a consistent mental model makes it much easier to understand what the software is asking for—and to recognize when a result doesn’t make sense.

Datum

The datum is an imaginary vertical reference plane chosen by the aircraft designer. All distances used in weight and balance calculations are measured from this plane. The datum itself is arbitrary, but once defined it must be used consistently. Nothing physical happens at the datum; it simply establishes where “zero” is.

Arm

An arm is the distance from the datum to where a weight acts. It tells you where that weight is located along the airplane.

Moment

A moment represents the rotational effect of a weight about the datum. It is calculated as:

Moment = Weight × Arm

Moments are not averages. They are weighted contributions that allow the effect of multiple weights at different locations to be summed correctly.

Center of Gravity (CG)

The CG is the result of the calculation, not an input. It is found by dividing the total moment by the total weight:

CG arm = Total Moment ÷ Total Weight

This division produces a weighted average location that represents where the airplane balances.

Mean Aerodynamic Chord (MAC)

The MAC is a representative wing chord that reflects how lift is distributed across a non-rectangular wing. The POH defines both the length of the MAC and the location of its leading edge relative to the datum.

%MAC

%MAC expresses the CG location as a percentage of the MAC, measured aft from the MAC’s leading edge. It is aerodynamically meaningful and commonly used in POHs to define CG limits.

In practice:

- Weight and balance calculations are performed in inches from the datum

- CG limits are often expressed in %MAC

- Converting between the two is simply a change of coordinate system, not a change in physics

How this fits together

Garmin Pilot works by summing weights and moments to compute a CG in inches. That CG can then be compared directly against envelope limits derived from the POH, even when those limits originate in %MAC.

Setting Up Weight & Balance in Garmin Pilot

With the concepts out of the way, we can move on to the actual Garmin Pilot configuration. The key idea to keep in mind throughout this section is that nothing here is creative—we are translating POH data into a form Garmin Pilot understands.

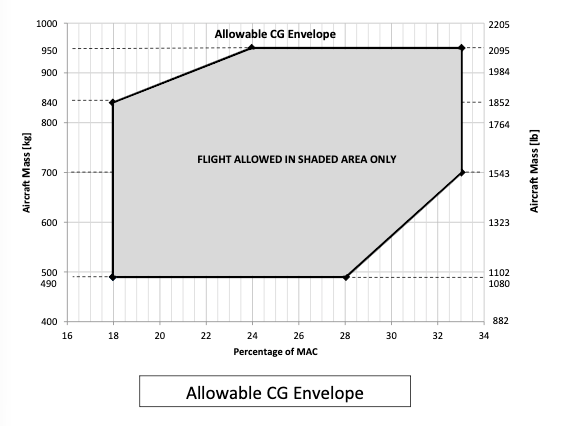

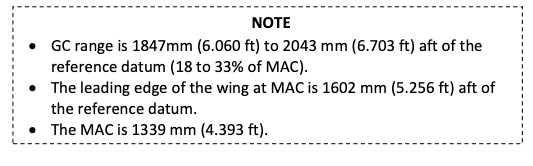

3.1 Defining the Normal Category Envelope

The Sling TSi operates in the Normal Category, so that is the envelope we define in Garmin Pilot.

Garmin Pilot requires the CG envelope to be entered as a series of points, connected in order. These points must be entered clockwise, or Garmin Pilot will issue an error and will not accept the envelop definition. This is one of those details that isn’t obvious until you get it wrong.

The Sling POH defines CG limits in %MAC, while Garmin Pilot requires inches from the datum, so the first task is converting those limits.

Converting %MAC to inches

From the POH we need two values:

- Location of the leading edge of the MAC (LEₘₐc), measured from the datum

- MAC length

The conversion formula is:

CG (inches) = LEₘₐc + (%MAC ÷ 100 × MAC)

In this setup:

- LEₘₐc = 1602 mm = 63 inch

- MAC = 1339 mm= 52.72 inch

Each forward and aft CG limit in %MAC is converted using this formula, and the resulting inch values become the x-coordinates of the envelope points in Garmin Pilot. The y-coordinates are the corresponding weight limits from the POH.

Once all points are entered, the envelope shown in Garmin Pilot should visually match the POH envelope when plotted in inches.

This is an important validation step. If the shape looks wrong, stop and recheck the inputs.

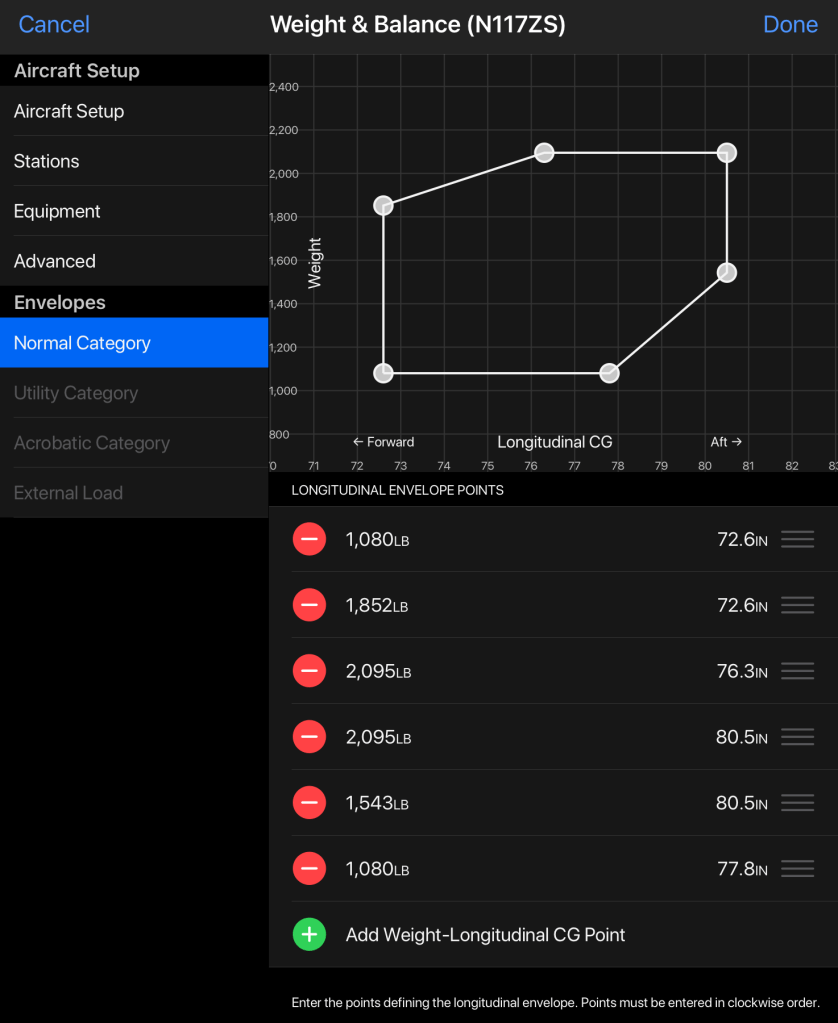

3.2 Defining Weight Stations

Next, we define the stations—the parts of the airplane where weight can change between flights.

For this post, stations are modeled at the row level, not individual seats. If the POH assigns the same arm to both seats in a row, only the total weight in that row matters for longitudinal CG.

Each station requires:

- A name

- An arm (from the POH)

- Units consistent with the rest of the profile (pounds and inches)

This abstraction keeps the model simple, realistic, and aligned with how people actually load the airplane.

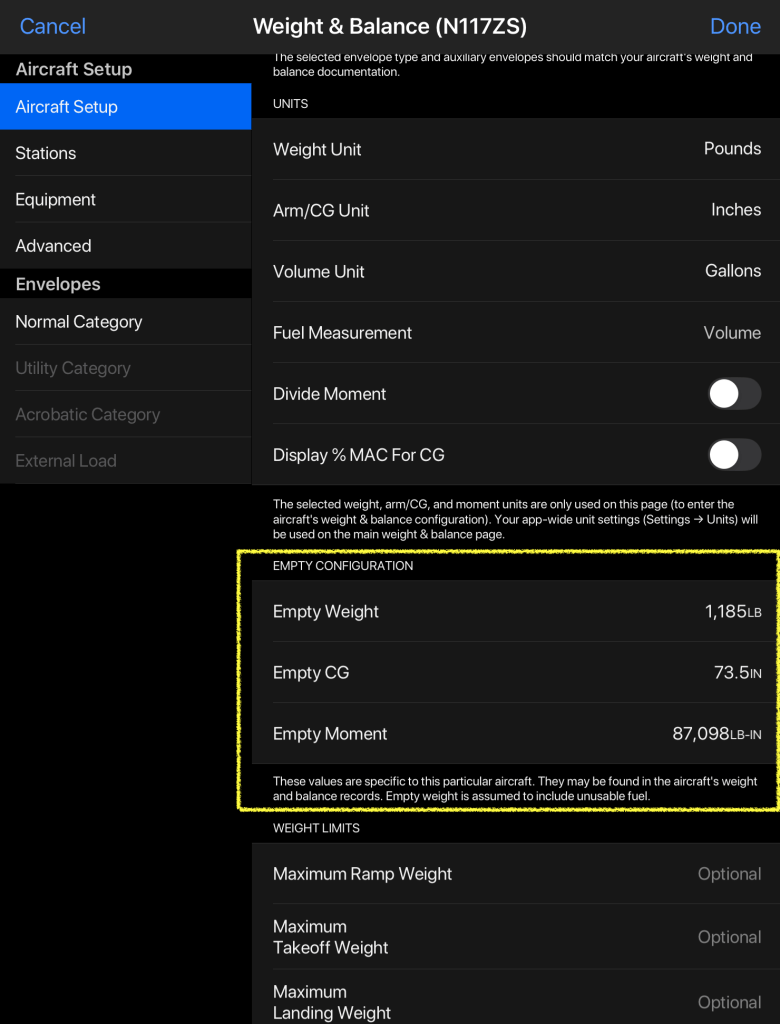

3.3 Aircraft Setup (Empty Weight Baseline)

Finally, we define the aircraft specific configuration itself.

This includes:

- Empty weight

- Empty CG location

- Empty Moment

At this stage, I am using reference data from a Sling TSi with a very similar configuration, including a parachute system. This allows the profile to be fully configured and validated now.

When my aircraft’s final weight and balance report becomes available, only these three values will change. Everything else—the envelope, stations, and workflow—will remain exactly the same.

Once all three sections are complete, Garmin Pilot will allow the aircraft profile to be saved, and the weight & balance tool becomes usable for scenario analysis.

The Aft CG Discussion: Context and Framing

Within the Sling TSi community, there has been ongoing discussion around aft center-of-gravity behavior, particularly in scenarios where the airplane is light on fuel toward the end of a flight. This comes up most often in parachute-equipped aircraft, where additional mass is carried aft relative to some non-parachute configurations.

This post does not attempt to adjudicate that discussion or re-evaluate certification data. Instead, it takes a more practical approach: assume the concern is real, then ask a more useful question—

Under what realistic loading conditions does aft CG actually become relevant for day-to-day flying?

A key point that often gets lost in informal discussions is that aft CG is usually not a takeoff problem. With fuel onboard, the CG is typically more forward. The aft shift happens gradually as fuel is burned, which means the most critical CG condition often occurs late in the flight, not at departure.

This is why the Sling POH explicitly calls for checking both takeoff and landing CG. The airplane you take off in is not the airplane you land.

When these elements combine unfavorably—light front occupants, heavier rear occupants, baggage aft, and low fuel—the CG can migrate toward the aft limit. None of this is mysterious; it is a predictable result of moments and arms.

The goal of the next section is to make this behavior visible.

Rather than relying on anecdote, we will use the Garmin Pilot model built earlier to run a set of realistic loading scenarios, focusing on configurations people actually fly. Each scenario will be evaluated at both takeoff fuel and landing fuel, so the CG migration over the course of the flight is explicit.

This shifts the conversation from “is there an aft CG issue?” to the more operationally useful question:

Does this specific loading, for this specific flight, remain comfortably within limits from start to finish?

A Note on Lateral CG (Left–Right Balance)

So far, this post has treated each seat row as a single station and focused only on total weight per row, not where individual occupants sit. That is intentional and correct for longitudinal CG, which is what determines stability margins and CG limits in the POH.

That said, Garmin Pilot does calculate lateral CG (you need to toggle the option in the Aicraft W&B config section). This allows it to account for left–right imbalance and can be useful for identifying a wing-heavy condition. However, for normal GA operations—including the Sling TSi—lateral CG is not a limiting safety parameter. Small left–right imbalances are expected, tolerated by the aircraft design, and easily corrected with trim or minor control input. If lateral CG were safety-critical, the POH would define lateral limits and require explicit tracking. It does not.

For the purposes of this analysis, the simplifying assumption is that occupants within the same seat row share the same longitudinal arm, and that any lateral imbalance is operationally insignificant. In other words, it is the total weight in each row that matters for CG limits, not which specific seat an occupant uses. Garmin Pilot’s ability to compute lateral CG does not change the conclusions here; it simply adds fidelity beyond what is required to evaluate longitudinal CG compliance and aft-limit behavior.

Scenario Analysis: Realistic Loads for a Parachute-Equipped Sling TSi

Before we jump into the scenarios, one key clarification: fuel matters a lot in the Sling TSi’s CG story. The fuel tank CG is forward relative to the aft baggage/rear-seat stations, so carrying fuel tends to pull the overall CG forward. That means a loading that looks “aft limited” at zero fuel may be perfectly acceptable at a realistic landing fuel state.

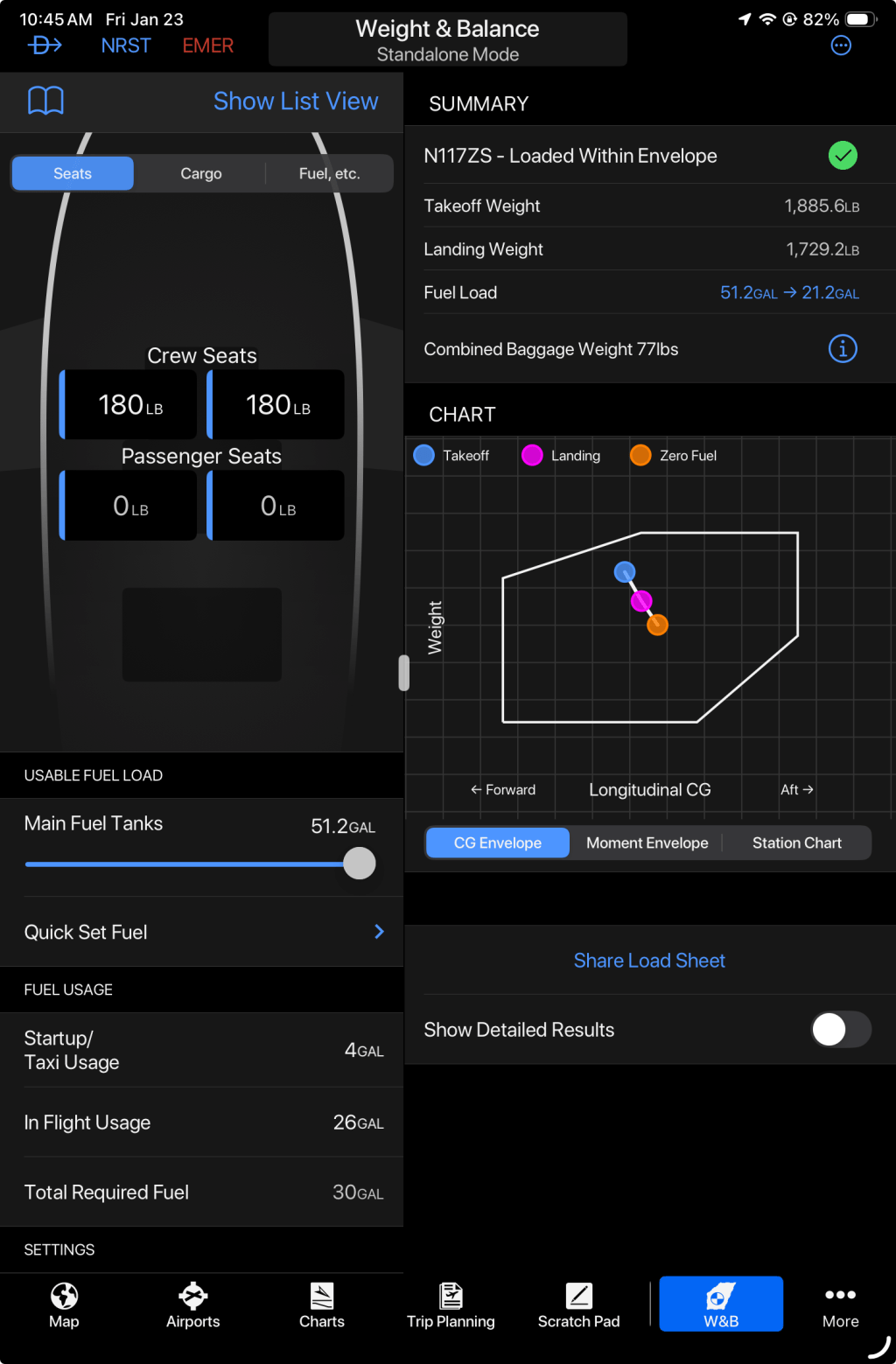

To make that visible (and avoid misleading conclusions), each scenario below is evaluated in two fuel states:

- Flight case (realistic landing): after burning 30 gallons, i.e. you return with ~21 gallons of fuel still onboard (not empty).

- Zero-fuel case (stress test): an intentionally extreme “empty tanks” case used to expose the aft-CG tendency.

This approach makes the takeaway practical: you don’t fly most missions at zero fuel, but understanding the zero-fuel behavior helps you see which loadings are inherently aft-biased and which are comfortably stable throughout normal operations.

I’m also using CDC-based representative weights to keep this repeatable:

- Average adult: 180 lb

- Child (10–12 years): 90 lb

For each scenario, I’ll show the Garmin Pilot setup workflow once, then present the configuration and the result as screenshots with short commentary.

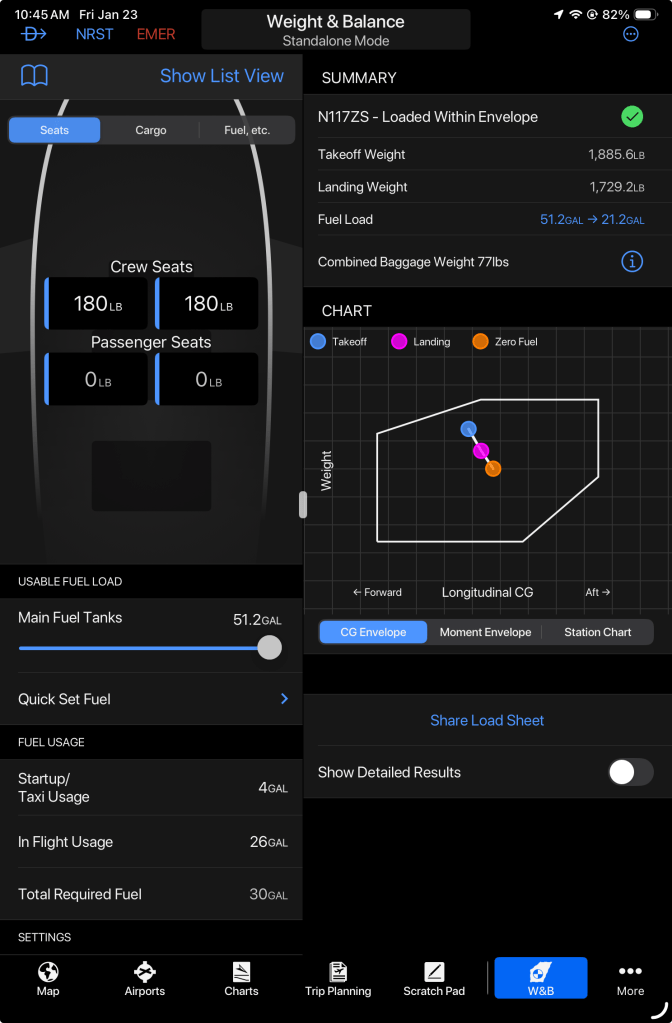

Scenario 1 — Two Adults + 50 lb Baggage (Baseline)

Configuration

- Front row: 2 adults = 360 lb

- Rear row: empty

- Baggage: 50 lb

- Fuel: evaluated at both (a) after burning 30 gal and (b) zero fuel

Result

- No issue in either fuel state. The aircraft remains comfortably inside the envelope with margin.

- There’s room for additional baggage (within gross weight limits), and CG remains well-behaved.

This is the “normal trip” baseline and a sanity check for the model.

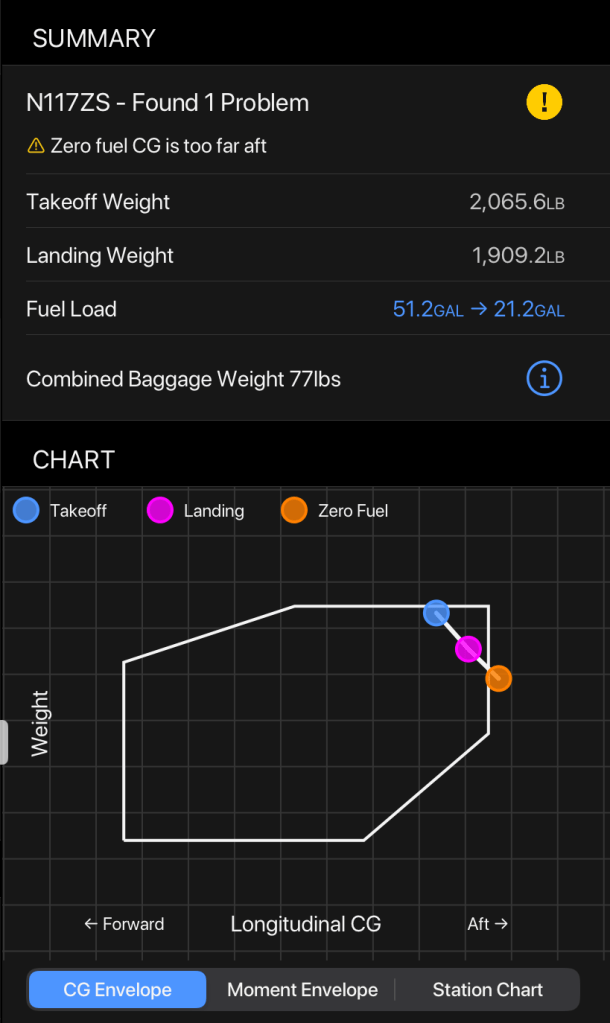

Scenario 2 — Three Adults + 50 lb Baggage (Fuel-dependent aft CG behavior)

Configuration

- Front row: 2 adults = 360 lb

- Rear row: 1 adult = 180 lb

- Baggage: 50 lb (aft baggage area)

- Fuel: evaluated at both (a) after burning 30 gal and (b) zero fuel

Result

- Flight case (after burning 30 gal): Within limits.

The forward fuel station keeps CG in range. - Zero-fuel case: Aft CG issue.

With the forward “ballast” of fuel removed, the combination of a rear passenger plus aft baggage pushes CG beyond/too near the aft boundary.

Mitigation (for the zero-fuel case)

- Moving ~35 lb of baggage forward (e.g., placing it in the rear passenger area rather than the aft baggage compartment) brings the CG back into limits.

This is the key nuance: with a realistic amount of fuel onboard, this loading works. The aft-CG concern emerges when fuel gets very low, because the airplane loses a forward CG contribution.

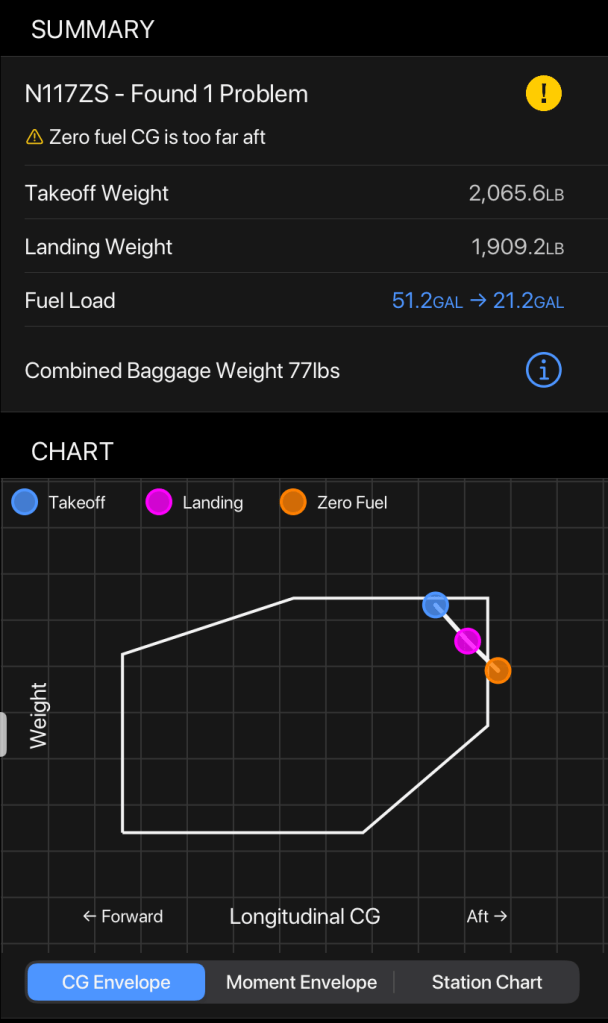

Scenario 3 — Two Adults + Two Kids + 50 lb Baggage (Also fuel-dependent)

Configuration

- Front row: 2 adults = 360 lb

- Rear row: 2 children = 180 lb

- Baggage: 50 lb

- Fuel: evaluated at both (a) after burning 30 gal and (b) zero fuel

Result

- Flight case (after burning 30 gal): Within limits (or very close, depending on exact numbers), because fuel pulls CG forward.

- Zero-fuel case: Aft CG issue (slight).

Removing the forward fuel contribution shifts the CG aft enough that the configuration becomes marginal or out of bounds.

Mitigation (for the zero-fuel case)

- Reducing baggage by ~10 lb (or shifting some of that weight forward) resolves the issue.

This is the most realistic “four humans” scenario for a TSi: kids in the back, adults in front. It can work in real missions where you land with fuel onboard—but it can still be tight in low-fuel conditions.

Scenario Summary and Takeaways

Looking across all scenarios, a few consistent patterns emerge.

First, for a parachute-equipped Sling TSi, the airplane behaves very comfortably in two-person configurations, even with meaningful baggage. CG margins are generous, and fuel state does not materially change the outcome.

Second, once you move to three people, the airplane becomes fuel-state dependent. With a realistic landing fuel state (in this analysis, after burning ~30 gallons), configurations that include a rear passenger and baggage are typically within limits. However, when fuel is reduced toward zero, the forward CG contribution from the fuel tank disappears, and the same configuration can migrate aft enough to require mitigation.

Third, four-person scenarios—even with children in the rear—are possible only with care. They may work for normal flights where fuel remains onboard at landing, but they tend to be tight and quickly become aft-limited in low-fuel conditions. This reinforces the practical reality that a parachute-equipped TSi is best thought of as a three-person airplane with flexibility, rather than a true four-person touring aircraft.

Most importantly, these results show that the aft CG discussion is not about a single “bad” configuration. It is about how CG migrates over the course of a flight, and how fuel acts as a meaningful forward counterbalance. Garmin Pilot makes this visible—but only if you evaluate more than a single snapshot.

Scenario Summary Table

| Scenario | Front Row | Rear Row | Baggage | Fuel State | Result | Key Takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: 2 adults + baggage | 360 lb | 0 lb | 50 lb | 30 gal burn | OK | Large CG margin, very flexible |

| 1: 2 adults + baggage | 360 lb | 0 lb | 50 lb | Zero fuel | OK | Fuel state irrelevant here |

| 2: 3 adults + baggage | 360 lb | 180 lb | 50 lb | 30 gal burn | OK | Fuel keeps CG forward |

| 2: 3 adults + baggage | 360 lb | 180 lb | 50 lb | Zero fuel | Aft CG issue | Mitigate by moving ~35 lb forward |

| 3: 2 adults + 2 kids + baggage | 360 lb | 200 lb | 50 lb | 30 gal burn | OK / Tight | Works, but limited margin |

| 3: 2 adults + 2 kids + baggage | 360 lb | 200 lb | 50 lb | Zero fuel | Aft CG issue | Reduce or shift ~10 lb baggage |

Final Operational Insight

The most useful habit to take away from this exercise is simple:

Always check CG at both takeoff fuel and realistic landing fuel.

With a properly configured Garmin Pilot profile, this becomes a quick, visual check rather than a source of uncertainty or surprise—and that’s the real value of doing the setup carefully.

Leave a comment