Back in 2005, a younger, more wide-eyed me walked into Galvin Flying at Boeing Field and took the plunge into general aviation with a Cessna 172S (N174GF). She was a fine ship, high-winged and ready to show me the clouds (just not in them—yet). I trained under the steady hand of Mike Oswald, a retired commercial pilot with wisdom and patience that would make a monk blush. Got my ticket on March 12, 2006. Started instrument training, and then… Hoquiam (KHQM) happened.

One hairy IMC flight, a cockpit full of steam gauges, and the sudden realization that my continued survival depended on a vacuum pump roughly as reliable as a ‘90s dot-com startup made me take stock. I stuck to VFR, DA40s, and a loyal relationship with airport diners. My last flight was in August 2009, just before Amanda and I pivoted into parenthood, work kicked into overdrive, and I realized I had officially checked out every airport meal within a 100-mile radius of a guy who rents airplanes too often and eats too many $100 burgers. Flash forward to September 29, 2024—I’m back, baby. Only this time, I’ve got a mission: build a Sling TSi, get that instrument rating, and fly cross-country like a caffeinated snowbird.

Here’s what I found when I came back.

The Updrafts: Things That Blew Me Away

EFIS: Glass for the Masses

When I first trained in the DA40 with the Garmin G1000, it felt like I’d stepped into the future—one filled with synthetic vision, digital engine readouts, and knobs that didn’t require a PhD in ergonomics to use. Fast forward 15 years, and what used to be cutting-edge is now practically basic economy. Today, you can get avionics that run circles around the original G1000 for a fraction of the price—and they’ll fit in the panel of a homebuilt airplane you assembled with your own two hands (and a few YouTube tutorials).

Enter the Garmin G3X Touch, the gold standard in GA EFIS systems. It’s intuitive, powerful, and integrated in a way that makes you feel like you’re flying with your own personal mission control. Want synthetic vision? Done. Engine monitoring? Of course. Flight director, VFR and IFR navigation, touchscreen interface, Bluetooth connectivity to your EFB? All in there. It’s a symphony of situational awareness—and it doesn’t require a type rating to understand.

And then there’s the Garmin G5. This tiny, affordable wonder has essentially ended the reign of the six-pack in anything that isn’t a certified museum piece. For a few thousand dollars, you get a rock-solid, solid-state, battery-backed attitude indicator that does everything its analog ancestors did—only better, faster, and without relying on the famously unreliable vacuum system. Bonus: it fits in a standard 3-1/8″ hole, just like its elderly forebears, making it a plug-and-play upgrade that feels like cheating.

What used to be reserved for high-end bizjets and Cirrus fanboys is now accessible to flight school 172s and homebuilders alike. The democratization of EFIS technology is one of the true success stories in GA over the last decade. It’s made flying safer, more enjoyable, and—most importantly—less dependent on the spiritual whims of a spinning gyro.

EFBs: Foreflight Made Me Say “Wait, What!?”

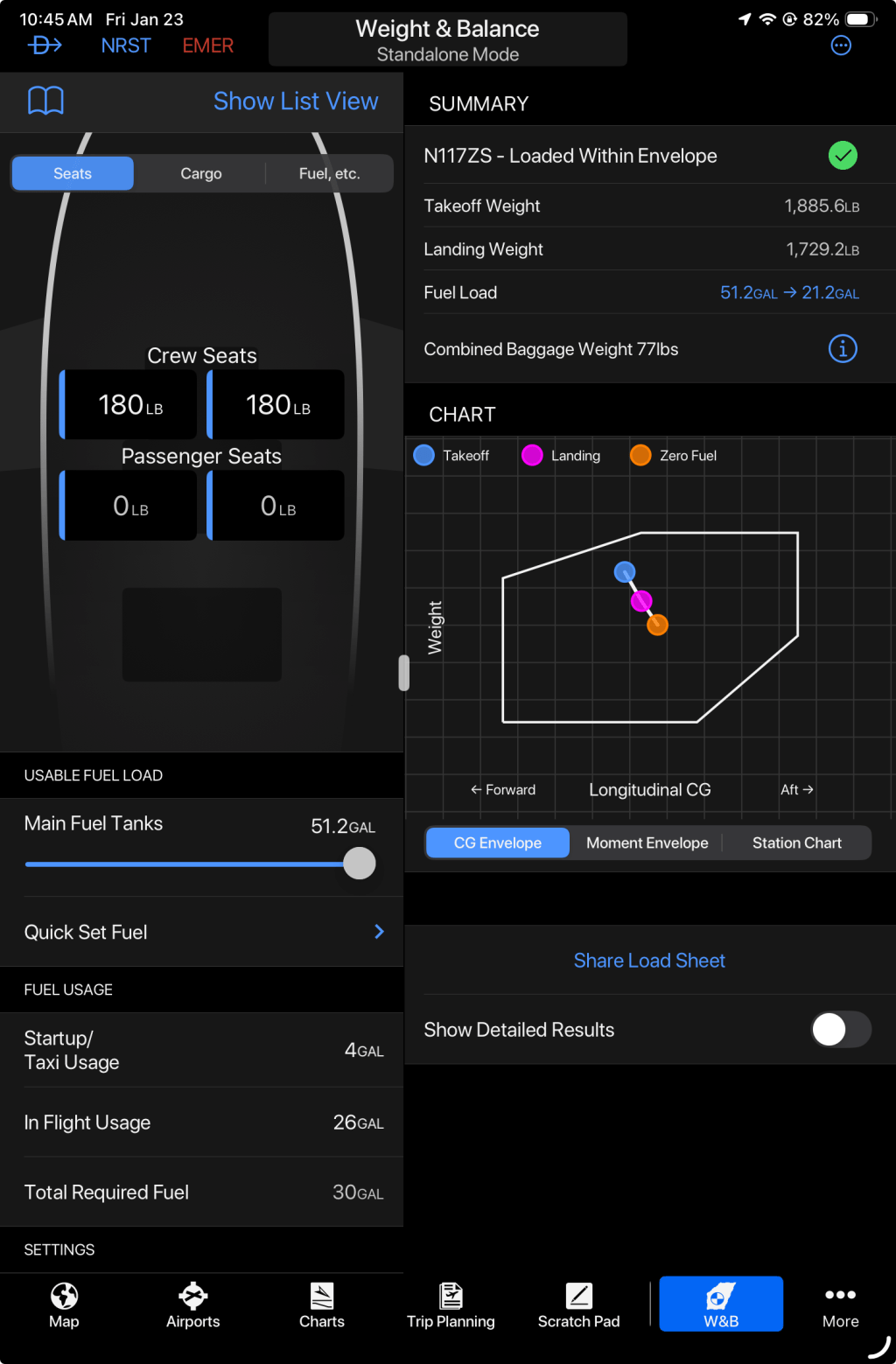

If EFIS is the glass cockpit revolution, then Electronic Flight Bags—EFBs for the initiated—are like strapping a co-pilot, meteorologist, flight planner, and air traffic controller to your knee. When I came back to flying and downloaded ForeFlight on my iPad, I thought I’d accidentally hacked into NORAD. This thing does everything. Preflight planning? Drag and drop your route and it’ll calculate time, fuel, weight & balance, winds aloft, and performance—no E6B or napkin math required.

Weather briefing? It’s no longer about deciphering TAFs like some ancient runes—ForeFlight gives you visual weather maps, radar overlays, METARs translated into human-speak, turbulence forecasts, and even icing predictions. During the flight, it’s basically omniscient: geo-referenced charts, traffic and terrain alerts (when paired with ADS-B), synthetic vision, glide rings, airport taxi diagrams with “own-ship” position… the whole thing feels like cheating, only it’s perfectly legal.

It’s also turned flight reviews into software demos. “Okay, show me how to do a diversion.” Opens ForeFlight, drags a finger, hits Direct-To. Boom. Done. The entire navigation, communication, and information workflow has collapsed into a single device you already own, regularly update, and use to binge-watch Netflix on layovers. And it syncs to your panel if you’re fancy.

In the days of paper charts, binder-sized kneeboards, and weight & balance forms you filled out with a pencil, ForeFlight feels like black magic. The only downside? You’ll spend more time updating databases and discovering new features than actually flying. But hey, that’s still more fun than arguing with DUATS ever was.

ADS-B: Finally, Some Eyes in the Sky

Back in 2006, traffic awareness meant squinting, praying, and hearing “I don’t have him either” on the intercom. Now, thanks to ADS-B, I know the exact location, altitude, and unfortunate call sign of the guy trying to cut me off on final. Bonus: real-time weather in the cockpit, which means my IFR planning doesn’t involve guessing cloud tops based on goat entrails and METAR poetry.

BasicMed: The Pilot’s Truce with the Medical Gods

There’s nothing “basic” about how revolutionary this is. The old Class 3 medical dance involved tracking down a flight surgeon, filling out forms like I was applying for security clearance, and worrying that having had a cold in 2008 would ground me for eternity. BasicMed says, “Relax, go to your doctor, be a responsible adult, and carry on.” It’s bureaucracy-lite, and I’m here for it.

Experimentals: The Hacker Ethos of Aviation

New to me, but not new to aviation. Experimentals are where aviation innovation actually happens—lighter airframes, better engines, glass cockpits, and prices that don’t make your wallet weep immediately. Building a plane sounded like a midlife crisis gone rogue until I realized it was the only way to actually own something cool without taking out a second mortgage. Also, I get to say “I built it” while pointing proudly like it’s a Lego set for grown-ups.

The Downdrafts: Things That Brought Me Back to Earth

Cost of Flying: Sticker Shock with a Propeller

Let’s get the ugly out of the way. It still costs a lot! Renting a 50-year-old 172 with a G3X? That’ll be $250 an hour, plus $88 for the instructor who’s probably 20 years younger than the plane. Want to buy a new C182? Sure, just give Textron $750,000 and they’ll throw in floor mats. Nothing—nothing—has been done in the last 15 years to bring prices down. GA is still largely a hobby for those with disposable income or stubborn dreams.

Innovation: Mostly Happens in Europe, Sorry

While I was away, I half expected the U.S. general aviation scene to have transformed into something out of The Jetsons. Instead, I came back to find that the big legacy manufacturers—Textron, Piper, Lycoming, Continental—are still clinging to their greatest hits from the 1960s like a dad refusing to retire his Pink Floyd vinyls. Meanwhile, Europe has been quietly eating our lunch.

European manufacturers like Diamond, Pipistrel, and Tecnam are pushing the boundaries with sleek composite airframes, modern fuel-efficient Rotax engines, hybrid and electric propulsion systems, and glass panels that look like they were designed this century. Rotax, in particular, has become the go-to for lightweight, reliable, and economical engines—especially for LSA and experimental aircraft—while Lycoming and Continental are still rolling out variations on the same old air-cooled, avgas-guzzling themes. (No shade… okay, maybe some shade.)

Electric GA? Pipistrel’s already flying them. Sustainable fuels? Europe’s way ahead. The U.S. seems stuck in a cozy little bubble of tradition, propped up by regulatory inertia and a culture that equates “new” with “probably illegal.” Cirrus is the one bright spot here, pushing forward with automation, safety systems, and composite design—but even they’re hamstrung by their reliance on old engine tech.

It’s not that America can’t innovate—it’s just that, in certified aviation, there’s little incentive and a lot of red tape. Want to fly something actually forward-looking in the U.S.? You’ll probably need to go experimental… or just import it from Austria.

The FAA: Still the DMV of the Skies

If you ever wondered what molasses in January looks like in bureaucratic form, just try engaging with the FAA.

Certified aircraft owners are trapped in a maze of paperwork, approvals, and “talk to your FSDO” nightmares. Want to replace a single instrument in your panel? Better hope it’s on the FAA’s nice list, or be prepared to file a mountain of paperwork, wait weeks (or months), and maybe get a field approval—if you’re lucky. Maintenance? You can’t legally change your own oil unless you’re an A&P, and even then, you’d better document every bolt you turned in triplicate. Want to upgrade to a more efficient prop or swap your vacuum system for something that wasn’t invented during World War II? Good luck. STCs (Supplemental Type Certificates) are often expensive, hard to find, and require approval processes that feel like applying for a moon landing permit

Even minor changes—like installing LED lights or swapping out old avionics for modern, off-the-shelf options—can trigger a bureaucratic avalanche. And when it comes to inspections, every squawk must be resolved to the letter, often by mechanics juggling the fine print of the FAR/AIM while also trying to run a business. It’s no wonder many owners look longingly at the experimental world, where you can install modern tech, innovate, and (gasp!) actually maintain your airplane without needing to call your FSDO or fill out a stack of forms that require a Rosetta Stone to decipher.

Where the Journey Begins Again

But here’s the thing. Even with the costs, the dinosaurs, and the bureaucratic sludge… flying is magic. The community is supportive and welcoming. The landscape of this country from 8,500 feet is breathtaking. And when you have your own airplane, you unlock the ultimate road trip—one with fewer gas station bathrooms and way better views.

I’m back not just for the nostalgia, but for the promise of adventure. The Sling TSi isn’t just a build project; it’s my ticket to the skies I missed for 15 years. And this time, I’m bringing tools, ForeFlight, oximeter, and my own plane.

Leave a comment