TL;DR

- Sling Aircraft now offers the DUC FlashBlack/TigerBlack 4-blade hydraulic propeller as a factory option, alongside traditional 3-blade props like the Airmaster and MT.

- More blades generally mean smoother operation, better climb performance, and reduced noise — but with a number of trade off in complexity, cost, efficiency.

- The difference in diameter between 3-blade and 4-blade options is small (72″ vs. 70.8″), and real-world testing shows only modest gains in takeoff roll and climb (≈5 sec and +150 fpm).

- For cross-country missions, 4-blade benefits are marginal; cruise performance is nearly identical.

- DUC’s is hydraulic actuated but it is integrated with the APR-1 controller providing a better interface than the blue knob.

- Airmaster, with its electric actuator and AC-200 controller, aligns better with my goal to build a modern, efficient aircraft — so that remains my first choice.

- If Airmaster becomes unavailable, DUC with APR-1 is a strong second option. MT is my last choice due to complexity and weight.

When One More Blade Makes You Think Twice

Sling Aircraft recently introduced the DUC FlashBlack and TigerBlack 4-blade propellers as a factory option for the Sling TSi, marking a notable shift in the aircraft’s configuration choices. Until now, Sling builders have predominantly selected 3-blade constant-speed propellers, such as the electrically actuated Airmaster or hydraulically actuated MT, both well-established options with documented performance characteristics.

The introduction of a 4-blade system reopens a nuanced but important design question:

How does propeller blade count affect aircraft performance, and where is the optimal trade-off for a light, high-performance GA aircraft like the Sling TSi?

On paper, the difference may appear minor — a shift from 3 to 4 blades — but the aerodynamic, acoustic, and mechanical implications are real. Blade count influences thrust, efficiency, tip speed, noise, vibration, and even ground clearance. In tightly engineered aircraft where weight, cooling, and climb rates matter, small changes can cascade into meaningful differences.

This post examines the aerodynamic theory behind blade count, compares the DUC 4-blade configuration to its 3-blade counterparts, and summarizes empirical findings from early Sling installations. I’ll also discuss my own build decision — where performance trade-offs met the realities of timing, system complexity, and a broader goal to build a modern, integrated aircraft.

Blade Count Comparison: 2 vs. 3 vs. 4 Blades — What Changes?

In light aircraft design, increasing the number of propeller blades from 2 to 3 to 4 is rarely just about aesthetics. Each step introduces aerodynamic trade-offs and performance consequences. Here’s a general comparison across the most common configurations in single-engine piston aircraft:

Thrust and Power Absorption

- 2-Blade: Most efficient on a per-blade basis, but limited in power absorption. Works well for lower horsepower engines (e.g. ≤160 HP) where propeller diameter can be kept large without hitting tip-speed limits.

- 3-Blade: A good balance — handles more power without increasing diameter significantly. Widely used in 150–200 HP aircraft.

- 4-Blade: Distributes power across more blades, allowing for shorter diameter while still absorbing full engine output. Particularly useful for high-output engines with tight clearance constraints or high RPM.

- Winner (for high power absorption): 4-blade

Cruise Efficiency

- 2-Blade: Generally has the lowest drag and best cruise efficiency. Fewer blades = fewer surfaces interacting with airflow and less parasitic drag.

- 3-Blade: Slight efficiency drop due to increased frontal area and interference drag, but modern blades narrow the gap.

- 4-Blade: Typically trades a bit more cruise efficiency — though well-designed 4-blade props can come close, especially with good twist and chord profiles.

- Winner (for max efficiency): 2-blade

- Trade-off: Efficiency losses with 3/4 blades are often minor — measured in a few percent.

Noise and Vibration

- 2-Blade: Tends to produce the most noticeable pressure pulses and cabin vibration. Tip noise can be significant at high RPM.

- 3-Blade: Smoother operation, reduced vibration due to more frequent and lower amplitude pressure waves.

- 4-Blade: Generally the smoothest and quietest — more pulses, but more evenly distributed. Often preferred when noise regulations or comfort are priorities.

- Winner (for comfort): 4-blade

Propeller Diameter and Ground Clearance

- 2-Blade: Requires large diameter to absorb power → may cause clearance issues, especially on tricycle gear aircraft.

- 3-Blade: Allows slightly shorter diameter while maintaining performance.

- 4-Blade: Can be noticeably shorter in diameter, offering more clearance — ideal for rough-field operations or aircraft with large tires.

- Winner (for clearance): 4-blade

Weight and Complexity

This is not solely a blade count issue — but rather a function of:

- Blade material (wood, composite, metal)

- Pitch control system: manual, hydraulic, or electric

For example: A 3-blade Airmaster is heavier than a 4-blade DUC not due to blade count, but because it includes a heavy electric actuator and controller system.

That said:

More blades = more balancing, slightly more hub weight, more surface area exposed to fatigue and wear. 2-blade props are the simplest and lightest overall.

Winner (for simplicity): 2-blade

But… total system weight depends more on hub and pitch control than on number of blades.

If 4 blades are smoother and quieter, why stop there? Why not 5, 6, or even 10?

The short answer: diminishing returns and increasing penalties.

- Aerodynamic efficiency drops: Each blade adds drag. After four, you gain very little in thrust but pay more in cruise speed and fuel burn.

- Increased interference: More blades interact with disturbed airflow from adjacent blades, reducing net thrust.

- Heavier and more complex: Every blade adds weight and requires precise dynamic balancing. Hubs get bulkier, and control systems more stressed.

- Lower RPM ceilings: To prevent blade tips from going supersonic, engines must run at lower RPMs — reducing prop efficiency.

- Cost and certification hurdles: More blades = more parts, more vibration testing, and higher costs — often not justifiable in light GA.

In short: For typical piston GA aircraft in the 100–300 HP range, 3 or 4 blades represent the optimal balance of performance, simplicity, and efficiency. Beyond that, you’re solving problems that light aircraft don’t have.

Where I Landed: The Propeller That Fits My Mission

After diving into blade count theory, performance trade-offs, and Sling-specific options, the question becomes practical: Which propeller did I choose for my own Sling TSi build, and why?

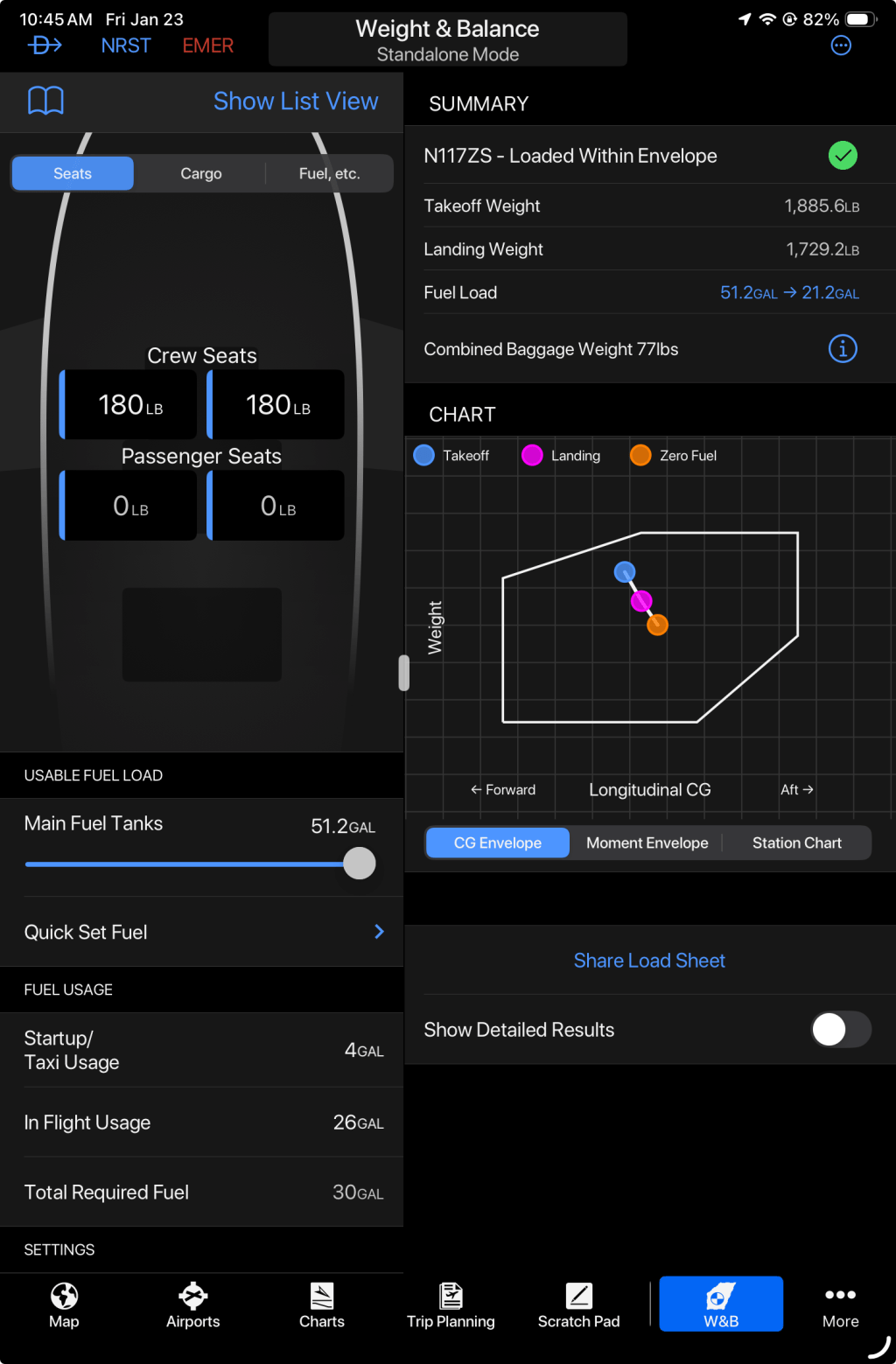

The recent Midwest Panel video on the DUC Tiger 4-blade propeller presents a compelling case. Their empirical results showed about a 5-second improvement in takeoff roll and an estimated 150 FPM climb rate gain over the 3-blade Airmaster. That’s meaningful, especially for short-field operations. They also confirmed what I observed in the specs: the diameter difference is minimal — the DUC Tiger comes in at 70.8 inches, while the Airmaster is 72 inches. This is not a radically different prop geometry, just a different approach to achieving the same aerodynamic goals.

So the performance upside is real — but modest. And with that in mind, I looked at the decision through the lens of my two key missions:

Building a Modern Airplane

For me, this project is as much about engineering philosophy as it is about performance. I’m building a Sling TSi to be clean, efficient, and modern — and to me, that includes the systems under the cowl, not just the aesthetics in the panel.

The DUC propeller uses a hydraulic actuated pitch system, while the Airmaster uses an electric pitch control system with a digital controller. That matters. While DUC does offer the Flyboy APR-1 controller, which provides automated, user-friendly pitch settings equivalent to Airmaster’s AC-200C controller (cruise, climb, T/O presets), my hesitation isn’t about interface usability. It’s about architecture.

Hydraulic constant-speed propellers are a design that dates back over 80 years. They’ve served aviation well — but in an experimental aircraft built in the 2020s, an electrically actuated propeller with fewer moving parts and simplified installation just aligns better with my goals.

So from a systems perspective, Airmaster remains my top choice.

Mission: Cross-Country Flying

My primary use case isn’t short-field work or aerobatics — it’s cross-country travel. Long legs, IFR, efficient cruise.

And while the 4-blade DUC Tiger does offer improvements in takeoff and climb, the cruise performance is functionally identical to the 3-blade Airmaster. No major gain in KTAS. No significant difference in fuel burn. Just smoother operation, slightly quieter in cruise. Those are nice-to-haves — but not mission-defining for me.

In a cross-country context, the benefits of the fourth blade are marginal, while the electric simplicity of the Airmaster aligns better with my goals and the mission profile.

Contingency Thinking

That said, the DUC prop is a solid product. If, as discussed in my earlier post, the Airmaster is no longer an option for the Sling TSi due to supply chain or factory integration issues, and if timing allows, I would likely opt for the DUC with the APR-1 controller. It delivers modern usability, a strong performance profile, and smoother operation. MT remains my last-choice option, due to its cost, hybrid carbon fiber/wood construction (versus fully carbon fiber) and expensive RS controller option.

As of this writing, I’m still awaiting final confirmation from the factory on whether the Airmaster is viable for my TSi. But I know where I stand.

Stay tuned.

Leave a reply to Sierra Cancel reply