TL;DR: Lead-acid batteries remain the low-cost, proven option: heavy, short-lived, and maintenance-prone, but simple and predictable. Lithium (LiFePO₄) batteries bring major advantages — lighter weight, stronger starts, stable voltage, and longer lifespan — at the price of higher upfront cost and reliance on electronics. The choice comes down to whether you value simplicity and price, or performance and efficiency.

Batteries are the heart of a general aviation airplane’s electrical system. They’re what get your engine started on a frosty morning and what keep your avionics glowing happily if the alternator takes a coffee break mid-flight. For decades, GA pilots have relied on trusty lead-acid batteries — the same chemistry that cranks your car. But in recent years, lithium batteries (specifically lithium iron phosphate, or LiFePO₄) have started showing up under cowls, promising dramatic weight savings and better performance.

In this post, we introduce our new paper — Lead-Acid vs. Lithium Batteries in General Aviation: Trade-Offs and Considerations. The paper goes into far more detail on the subject, but what follows is the big-picture summary in blog form.

The Basics: What’s Inside the Box?

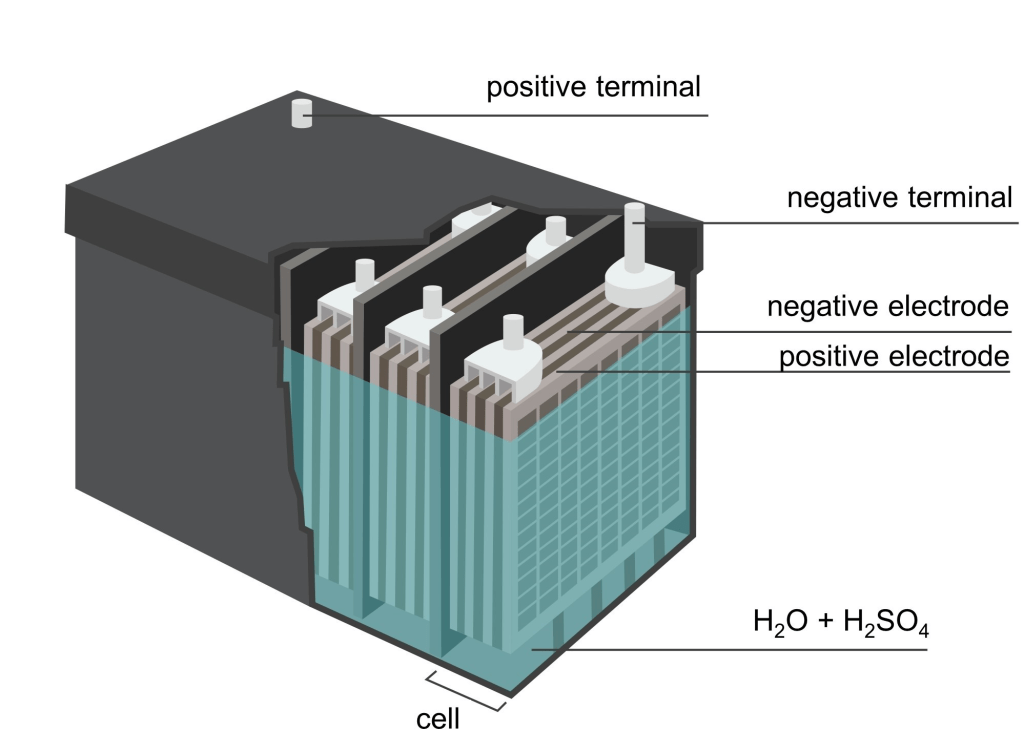

Lead-acid batteries are as old as aviation itself. They generate electricity by reacting lead plates with sulfuric acid, and each 12-volt battery is simply a stack of six of these cells. Their strengths are simplicity, reliability, and low upfront cost. They’re like that old pickup truck in the barn — a little creaky, but it always starts eventually. Their downsides are weight (they’re heavy for the energy they hold) and limited performance under stress.

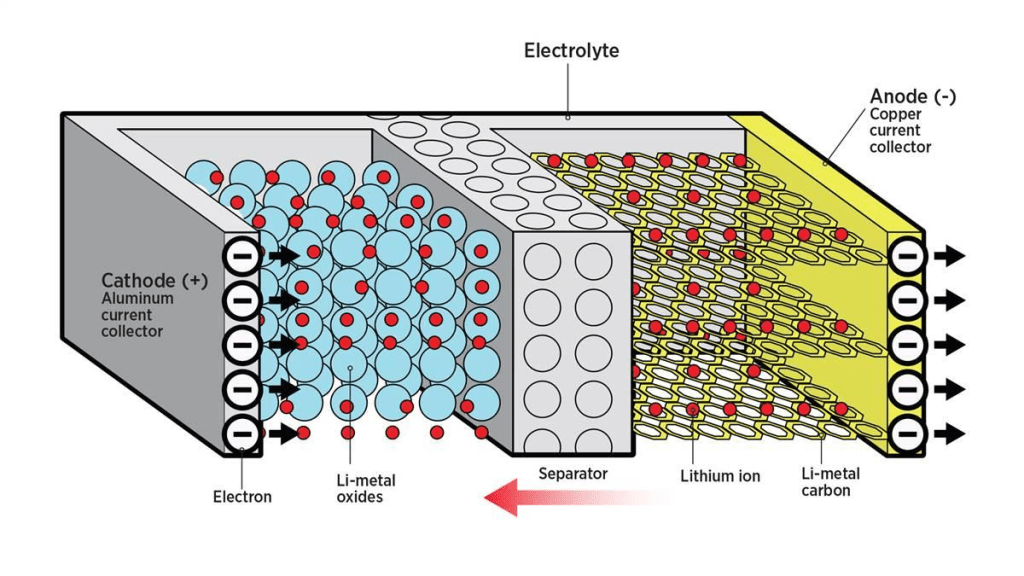

Lithium (LiFePO₄) batteries, by contrast, move lithium ions between electrodes made of lightweight materials, achieving three to five times the energy density of lead-acid. They also include a Battery Management System (BMS), which acts like a built-in guardian angel: it monitors the health of the cells, prevents overcharging, and shuts things down if something goes wrong. Lithium batteries are the sleek EV of the aviation world — lighter, smarter, and quicker off the line, but not without quirks.

Performance: Power to Spare

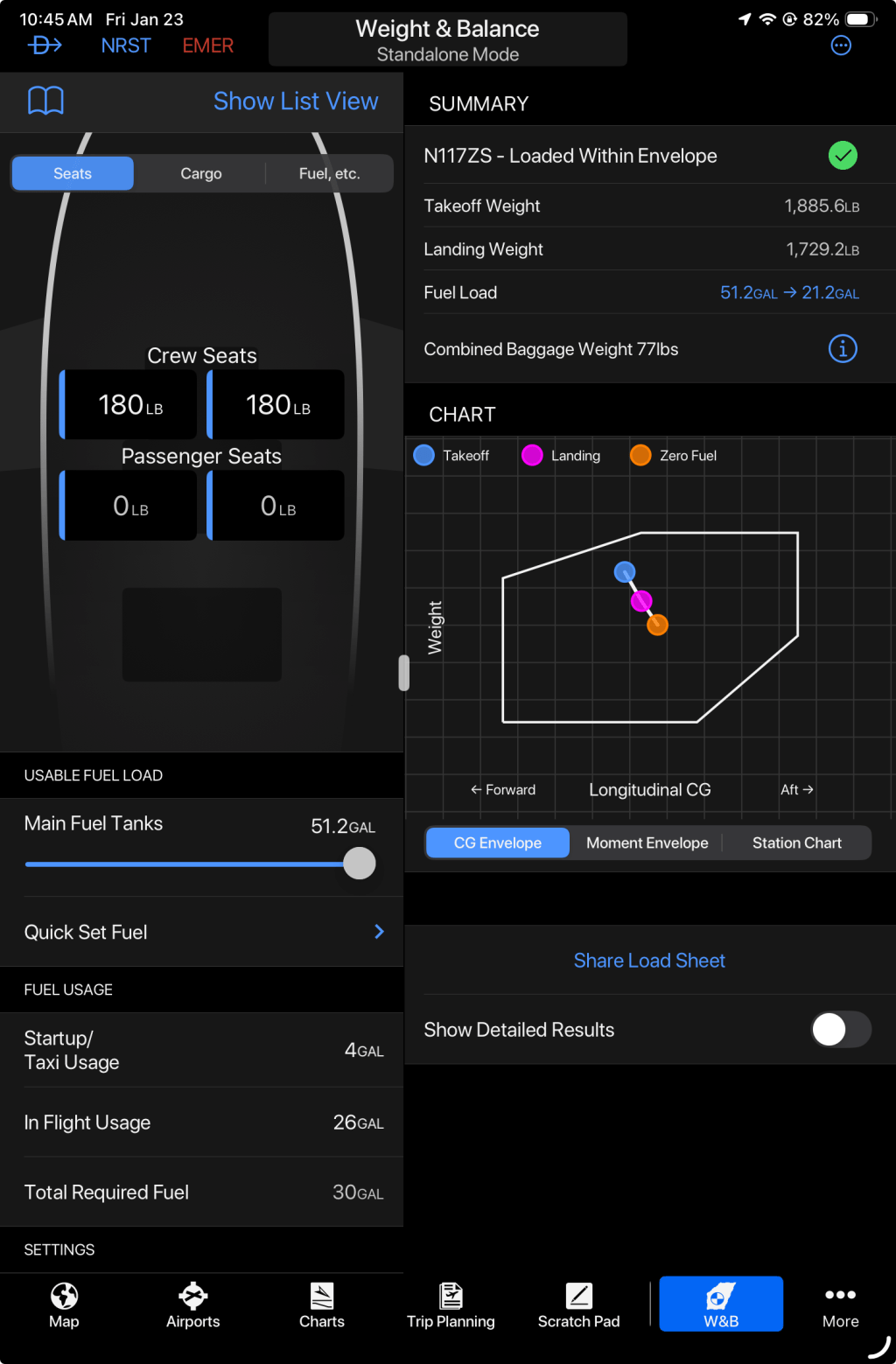

Weight savings are the headline feature. A typical GA lead-acid battery tips the scales at around 20–25 pounds, while an equivalent lithium battery comes in at just 5–8 pounds. That 15–20 pound reduction is free useful load: an extra passenger’s overnight bag, a few more gallons of fuel, or even just better CG balance. As one pilot on Van’s Air Force forum put it after swapping his Odyssey for an EarthX: “It was like pulling a brick out of the nose.”

Engine starts feel noticeably different. Lead-acid batteries can sag below 10 volts during cranking, dimming or rebooting your panel. Lithium holds voltage higher and delivers more cranking amps, so the starter spins faster and avionics stay online. A Mooney owner on Mooneyspace remarked: “First time I hit the starter with the lithium in, it felt like my prop was on steroids.” Especially in cold weather, this difference can be the line between a quick, clean start and a flooded engine.

Voltage stability is another quiet win for lithium. Lead-acid batteries steadily bleed voltage as they discharge. Lithium, on the other hand, holds a flat line until it’s nearly empty. For avionics and radios, that means you get consistent, stable power for nearly the entire discharge cycle. An RV builder on VansAirForce summed it up: “With lead, you watch the volts fade. With lithium, it’s rock steady — until the lights go out.”

Endurance: The Fine Print

Lead-acid batteries give you a graceful decline as they die. Lights dim, radios crackle, and you usually have some warning. The downside is that much of their rated capacity is effectively unusable under real loads, because avionics won’t operate well at the lower voltages.

Lithium batteries flip that script. They provide nearly all their rated capacity at usable voltage, then the BMS cuts power abruptly to prevent damage. That means great performance until the end, but little grace period. Pilots have adapted by wiring the EarthX warning light to the panel or by flying with dual-battery setups. As one Sling builder joked: “It’s like flying with a teenager — full of energy until suddenly they’re done, and you better be on the ground.”

Cost and Maintenance

Upfront cost is the main sticking point. A lead-acid battery might set you back $300–$400, while an EarthX or similar lithium will run $400–$900. Certified lithium batteries from True Blue Power can cost thousands.

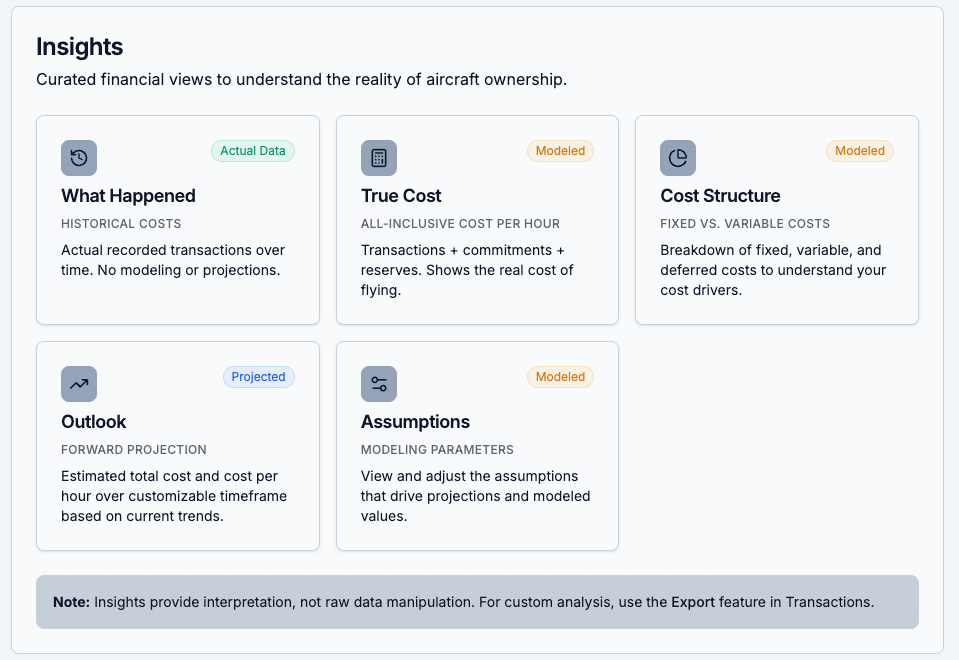

Lifespan, however, levels the playing field. Lead-acid typically lasts 3–5 years, sometimes less if neglected. Lithium can stretch to 8–10 years with thousands of cycles. Over a decade, you might replace two or three lead-acid batteries versus one lithium, which makes the economics surprisingly close.

Maintenance is easier with lithium. Lead-acid requires regular charging, hates deep discharges, and can suffer from sulfation if left partially discharged. Some even need electrolyte checks. Lithium is nearly maintenance-free — the BMS takes care of itself, and self-discharge rates are so low they can sit for months and still crank strong. Just don’t hook one up to a charger designed for desulfating lead-acid; that’s a recipe for confusion or damage.

Safety and Quirks

Lead-acid hazards are familiar: venting hydrogen gas during charging, potential acid leaks, and corroded terminals. They’re generally safe if maintained and installed properly, but they don’t protect themselves if abused.

Lithium (LiFePO₄) earned its bad rap from high-profile fires in consumer electronics and the Boeing 787’s early batteries. But LiFePO₄ is a much more stable chemistry than lithium-cobalt, and aviation-grade batteries include robust BMS safeguards. EarthX and True Blue both have millions of hours of flight time behind them with strong safety records. The catch is that safety depends on the electronics — if the BMS shuts down, you lose the battery abruptly.

Cold weather brings quirks for both. Lead-acid loses much of its cranking capacity when cold-soaked. Lithium maintains cranking power but shouldn’t be charged when below freezing, which is why many have internal heaters or procedures like “turn on pitot heat for a minute before start” to warm them up. Pilots in northern climates learn to preheat the airplane either way.

Real-World Reports

The experimental community has led the charge on lithium adoption. Builders of RVs, Slings, and other kitplanes rave about the weight savings and reliable starts. EarthX has become the de facto choice, with widespread positive reports. Many IFR pilots add redundancy by running two smaller lithium batteries or pairing one with a backup alternator, which still weighs less overall than a single lead-acid.

On the certified side, adoption is slower but picking up. True Blue Power has offered FAA-certified lithium batteries for over a decade, mainly in turboprops and jets, and EarthX introduced its TSO-approved ETX900 for piston singles. A few Cirrus and Piper models now offer lithium as factory equipment. Feedback is positive: owners report smoother starts and less maintenance. Still, some pilots remain cautious, waiting for the legacy brands like Concorde and Gill to release lithium options.

Across forums, one theme repeats: once pilots switch, few want to go back. As one AOPA writer summed it up: “Even though lithium had a rocky start, the benefits were just too important to ignore.”

Comparison at a Glance

| Feature | Lead-Acid | Lithium (LiFePO₄) |

|---|---|---|

| Weight | Heavy (20–25 lbs typical) | Light (5–8 lbs typical) |

| Energy Density | ~30–50 Wh/kg | ~150–200 Wh/kg |

| Engine Starts | Voltage sag, slower cranking | Strong, fast cranking, stable voltage |

| Voltage Curve | Gradual decline, warning as it fades | Flat until sudden BMS cutoff |

| Endurance | Less usable capacity under load | Higher usable capacity, abrupt cutoff |

| Lifespan | 3–5 years typical | 8–10 years possible |

| Maintenance | Needs charging, checks, sulfation risk | Nearly maintenance-free, BMS managed |

| Safety Risks | Hydrogen gas, acid leaks | Rare thermal events, BMS shutdown |

| Cold Weather | Cranking power drops sharply | Cranks well, but can’t charge <0°C |

| Upfront Cost | $300–$400 | $400–$900+ (certified in $1000s) |

| Overall | Cheap, proven, predictable | Light, powerful, longer-lasting |

The Bottom Line

Lead-acid and lithium batteries each have their place. Lead-acid is the proven workhorse: affordable, familiar, and predictable in how it fails. But it’s heavy, short-lived, and needs regular attention. Lithium, particularly LiFePO₄, is the newer contender: light, powerful, long-lasting, and nearly maintenance-free, but with higher upfront cost and a reliance on electronics.

For many GA owners, the choice comes down to priorities: if simplicity and price are top of the list, lead-acid still works. If performance, efficiency, and weight savings matter more, lithium becomes very hard to ignore.

After weighing the trade-offs for my own build, I decided to go with the EarthX ETX900. At just under 5 pounds, it saves over 15 pounds compared to a typical lead-acid, while still providing excellent cranking power and stable voltage for my Rotax 916iS and dual Garmin G3X avionics. It’s also available in a TSO-certified version, which speaks to its maturity and reliability in the GA community. For my mission profile, the ETX900 hits the sweet spot of weight, capacity, and proven real-world use.

Leave a comment