TL;DR: Emergency Autoland has moved from impressive demos to real-world use, forcing a new question for general aviation: not whether an airplane can land itself perfectly, but how much automation is needed to avoid the worst possible outcome. This post breaks Emergency Autoland down into its fundamental requirements — deciding where to land, flying a stabilized approach, managing energy, touching down, and stopping — and then evaluates those requirements against the actual configuration of my Sling TSi. Rather than treating Autoland as a monolithic, high end-only capability, the article looks at what parts of the problem are already solved by modern Garmin avionics, what additional authority or hardware would be required, and where the real gaps remain.

From there, the post introduces the idea of a Emergency Landing Assist (ELA): a deliberately constrained, experimental-friendly approach that aims for survivability rather than perfection. By extending concepts we already trust — like ESP and Smart Glide — and accepting shared responsibility with a passenger for tasks like power reduction or braking (or optionally adding simple actuators like a throttle servo and yaw motor), Emergency Landing Assist (ELA) introduces a third outcome in pilot-incapacitation scenarios. Even if the pilot never recovers, the airplane can still land under control — in the majority of circumstances — and for much of GA, that may be the most meaningful safety improvement available.

Yesterday’s Sci-Fi, Today’s Safety Net

A little over a decade ago, some of the safety features we now take for granted in modern general aviation panels felt almost indulgent — clever ideas that seemed better suited to jets, or at least to highly controlled environments. Not because experimentals couldn’t adopt them, but because the idea of software actively intervening still made many pilots uneasy.

In 2015, Garmin introduced Electronic Stability Protection (ESP) to the experimental world through the G3X platform. Envelope protection, automatic intervention near stalls or overspeeds, even gentle nudges back toward wings-level — all delivered as a software update. At the time, ESP felt intrusive to some and futuristic to others. Today, it’s quietly armed in the background of countless experimental aircraft, rarely noticed and occasionally life-saving.

A few years later, Smart Glide followed a similar trajectory. Tie engine-failure detection to navigation, performance modeling, and flight guidance, and suddenly the airplane can point itself toward the best available runway while the pilot deals with everything else. Again, no new physics — just tighter integration and a growing willingness to let automation take the lead in narrow, high-stress scenarios.

The next major inflection point came around 2020, when Emergency Autoland crossed from impressive capability into mainstream general aviation consciousness. When Cirrus made Autoland a standard feature on the Vision Jet — and later expanded its availability across high-end GA platforms — this kind of automation stopped being a distant promise. For the first time, an airplane routinely flown by owner-pilots could, in an emergency, choose a runway, fly the approach, land, stop, and guide the occupants through what comes next.

More recently, Autoland stopped being something we mostly saw in polished demos and marketing videos. It was used in a real emergency, with real people onboard, and it worked.

In a Beechcraft King Air equipped with Garmin avionics, Autoland was activated during an actual in-flight emergency involving pilot incapacitation. The system selected an airport, flew the approach, landed the aircraft, brought it to a stop, and ensured that everyone onboard survived. No test pilots. No safety chase plane. Just a machine doing exactly what it was designed to do on someone’s worst possible day.

That moment matters. Aviation technology often lives in a long transition between “possible” and “trusted.” ESP and Smart Glide made that journey quietly. Autoland is now doing the same — but with much higher stakes.

Which leads to an obvious and slightly uncomfortable question:

If Autoland is no longer science fiction in certified GA, how far away is it from an aircraft like my Sling TSi?

This post is a thought experiment. We’ll deliberately set certification aside and start from a very specific baseline: my actual airplane, as configured today. From there, we’ll explore what would need to change — and what already exists — for Autoland to move from a jet-level safety feature to something that might one day be plausible in the experimental world.

What Autoland Actually Is (and Is Not)

Before applying the idea of Autoland to a Sling TSi, it’s worth being precise about what Autoland actually means — and just as importantly, what it does not mean.

Autoland is not a smarter autopilot. It’s not “LPV to minimums with a better flare.” And it’s definitely not an AI making creative decisions on the fly. In systems like Garmin Emergency Autoland, it’s best understood as a predefined emergency playbook, executed end-to-end by the airplane when the pilot can no longer do the job.

At a high level, Autoland does three things, in order:

First, it decides where to land. That decision is deliberately conservative. The system looks at runway length, terrain, weather, winds, available approaches, fuel state, and aircraft performance — and then aggressively filters options. The goal is not “closest airport” or “best airport,” but “an airport where this specific airplane can land safely with minimal drama.”

Second, it flies the airplane to the runway and lands it. This includes navigation, descent planning, configuration changes, speed control, flare, touchdown, and rollout. By this point, the system isn’t assisting the pilot — it is the pilot. The automation owns pitch, roll, power, and configuration, continuously cross-checking sensors and actuator responses to make sure the airplane is actually doing what it was told.

Third, it finishes the job on the ground. Autoland doesn’t end at touchdown. It slows the airplane, keeps it on the runway, brings it to a stop, and then shifts into a human-centric mode: securing the airplane and telling the occupants what to do next. This is a small detail with big implications. Autoland is designed for passengers who may have never touched an airplane control in their lives.

Equally important are the things Autoland is not trying to do.

It’s not trying to land at the pilot’s preferred airport.

It’s not trying to thread weather or salvage a marginal situation.

Autoland is intentionally boring. It enforces narrow operating envelopes, rejects risky options early, and gives up quickly if something doesn’t behave as expected. If it can’t find a landing option it likes, it will say so — loudly and early — rather than pressing on.

This distinction matters, because it explains why Autoland is harder than it looks. Flying an approach is something many modern autopilots can already do. Owning every step from decision-making to stopping on the runway, with no pilot backup, is a fundamentally different level of responsibility.

With that mental model in place, we can now do the interesting part: start from my actual Sling TSi configuration and ask how close — or how far — it already is from supporting something like this.

Starting Point: My Sling TSi as It Exists Today

Before imagining what would need to be added for Autoland, it’s important to be clear about the baseline. This thought experiment doesn’t start from a generic kit airplane or a hypothetical future build. It starts from my actual Sling TSi, configured the way it is today.

At a high level, the airplane already checks many of the boxes people instinctively associate with “advanced automation.”

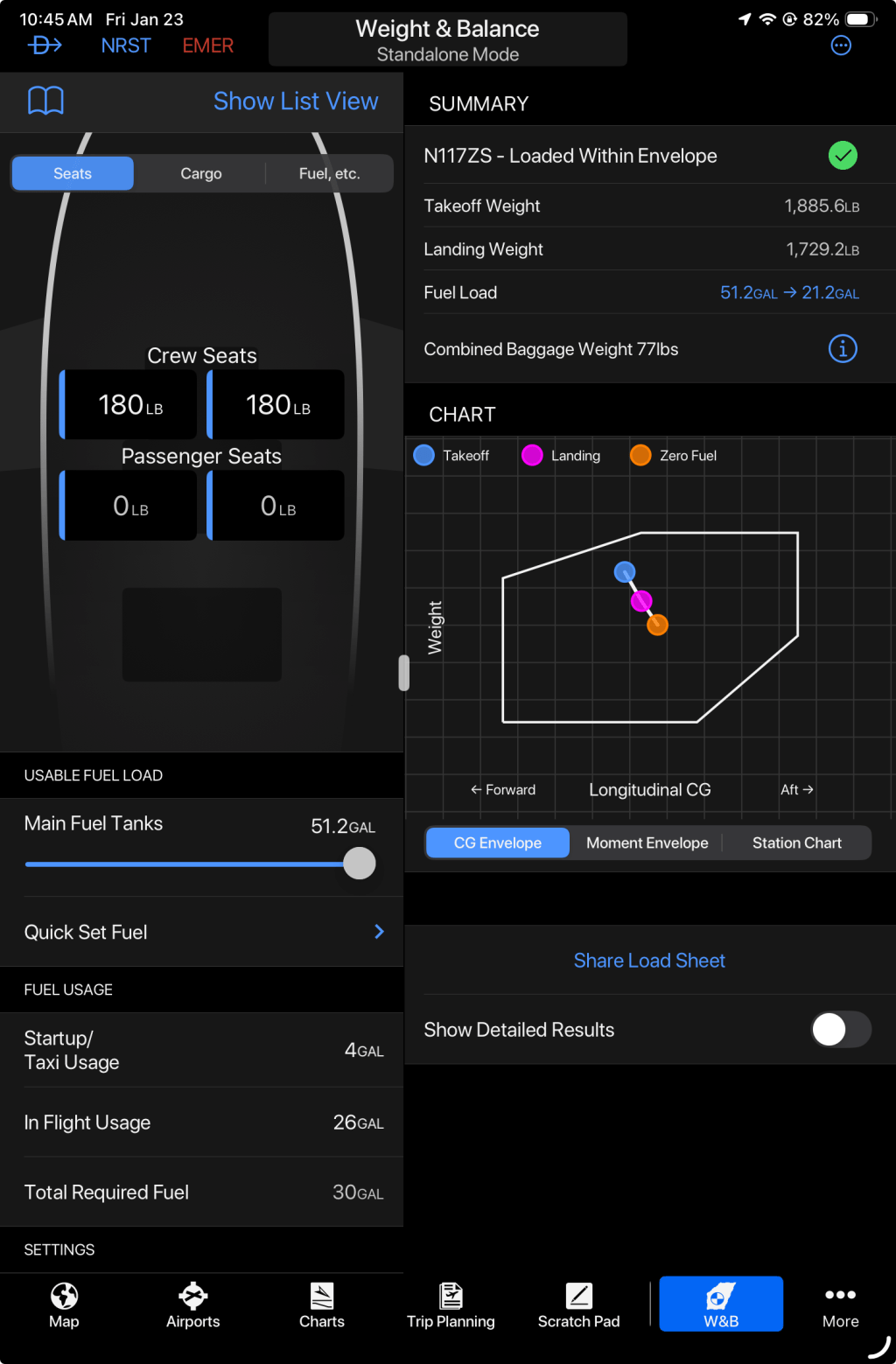

On the avionics side, the aircraft is built around a modern Garmin glass stack: dual G3X displays, a GTN 650Xi for IFR navigation, a G5 backup instrument, and a GFC 507 autopilot. This setup already supports fully coupled IFR approaches, vertical navigation, envelope protection, ESP, Smart Glide, and tight integration between navigation, flight guidance, and engine monitoring.

From a sensing perspective, the airplane is well equipped. Dual ADAHRS provide attitude and air data redundancy, and a GHA 15 radar altimeter adds precise height-above-ground information — a key input for any system that needs to manage the last few seconds before touchdown. This is not a “glass-lite” experimental panel; it’s closer in spirit to what you’d find in aircraft that already support advanced automation.

On the electrical side, redundancy is a design priority. The airplane has multiple alternators, a solid-state main battery, and backup batteries dedicated to avionics. Losing a single power source does not immediately mean losing the ability to navigate, communicate, or control the airplane. That matters because Autoland is explicitly designed for scenarios where something has already gone wrong.

Configuration management is also more automated than many people assume. The Sling uses electric flaps, and flap deployment is already mediated by the avionics. The system enforces speed limits and inhibits unsafe commands, which means flap movement is no longer a purely manual, pilot-judgment-only action. That’s an important distinction when thinking about higher levels of automation.

Where things become more traditional — and more interesting — is at the mechanical interface.

The throttle is mechanically actuated. There is no autothrottle or servo controlling engine power. Braking is symmetric only; there is no differential braking capability available to automation. Nosewheel steering is mechanically linked to the rudder pedals via pushrods, which means directional control on the ground is fundamentally tied to rudder authority rather than independent steering or braking.

Yaw control is another boundary. Today, the autopilot provides pitch and roll control, but no rudder servo is installed. That’s a perfectly reasonable choice for most missions — but it becomes a constraint when thinking about crosswind handling, alignment at touchdown, and rollout control without a pilot’s feet on the pedals.

Put together, this creates an interesting picture.

The Sling TSi already has the eyes, the brain, and the electrical resilience you would expect in an aircraft capable of sophisticated safety automation. What it lacks are what you might call robot limbs: the ability for the system to directly manage power, yaw, and braking without human input.

That gap is exactly where the rest of this thought experiment lives.

Breaking Autoland into Concrete Requirements

With the baseline established, we can reduce Autoland to its functional requirements, independent of brand, certification, or marketing language. This matters because every solution discussed later — a full Garmin system, a Emergency Landing Assist (ELA), or today’s Sling TSi — must ultimately satisfy the same underlying needs.

This table is the reference point for the rest of the article. If a proposed solution doesn’t map cleanly to one of these rows, it’s hand-waving.

| Requirement Area | What Autoland Must Do | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Decision-making (Where to land) | Select a suitable airport using aircraft performance, runway data, weather, terrain, airspace, and fuel/endurance limits | Autoland is not about convenience. It aggressively filters options until only boring but survivable remains. This mindset is foundational. |

| Guidance (Getting there) | Fly laterally and vertically with precision; plan descents; follow published approaches; continuously cross-check nav, attitude, and air data | This is the most mature part of the stack. Modern Garmin-equipped experimentals already do this extremely well. |

| Configuration management | Command flaps and trim at the right time; verify that configuration changes actually occurred | For Autoland, configuration changes are not suggestions. Authority, feedback, and failure detection are mandatory. |

| Energy management | Control airspeed and descent rate; coordinate pitch and power; transition cleanly to idle at the right moment | This is where Autoland diverges from a normal autopilot. Something functionally equivalent to autothrottle becomes necessary. |

| Landing (Last 200 feet) | Sense height above ground; execute a predictable flare; align with the runway; tolerate gusts without over-correcting | Small errors here have large consequences. This drives conservative envelopes and long-runway assumptions. |

| Rollout and stopping | Maintain directional control; decelerate predictably; stop on the runway; avoid excursions | Touchdown isn’t the end. This exposes hard truths about yaw authority, braking, and steering design. |

| Human interface | Provide a clear activation method; unmistakable annunciation; simple spoken instructions; post-stop guidance | Passengers are part of the system. Confusion is a failure mode, not a user error. |

| Resilience and supervision | Survive failures via redundancy; perform plausibility checks; confirm actuator response; disengage or re-plan when reality diverges | This is where Autoland stops being an avionics feature and becomes a true safety system. |

This table is deliberately uncompromising. It doesn’t say how these requirements must be met — only that they must be met somehow. The rest of the article explores two very different answers to that question: a full OEM Autoland, and a deliberately constrained Emergency Landing Assist (ELA) that aims for survival rather than perfection.

Thread One: If Garmin Offered a Fully Integrated Autoland for the Sling TSi

Let’s start with the cleaner, more disciplined thought experiment:

What if Garmin decided to treat the Sling TSi the way it treats the Vision Jet, TBM, or King Air?

Ignore certification hurdles. Assume commercial intent. Assume Garmin is willing to own the outcome.

Under those assumptions, Garmin would not deliver Autoland as a feature toggle or a clever software update. They would deliver it as a complete system, designed to remove ambiguity about who is in charge when things go wrong.

Garmin’s design philosophy: own the last inch

Garmin’s approach to Autoland has been consistent across aircraft types. The company does not rely on partial authority or pilot cooperation during the event. When Autoland is active, the system:

- owns the controls,

- owns the decision-making,

- and enforces a conservative operating envelope.

This is why Autoland shows up first in tightly integrated aircraft. The technical challenge isn’t flying the approach — it’s owning every actuator that matters, all the way to a full stop.

For the Sling TSi, that philosophy immediately implies new hardware.

Autothrottle: closing the energy loop

Garmin would treat autothrottle as non-negotiable.

In a Sling context, this would almost certainly take the form of a dedicated throttle actuation module installed inline with the existing mechanical throttle. The design priorities would be familiar from Garmin’s other servos:

- backdrivable with a defined manual override force,

- position sensing with internal cross-checking,

- fail-safe behavior that releases control on power loss,

- and tight integration with airspeed and descent logic.

The constant-speed propeller and FADEC-managed engine simplify this problem. Garmin would not attempt to micromanage RPM or engine parameters. The system would command throttle intent and continuously verify that the aircraft’s actual energy state matches expectations.

This is the single most important addition Autoland would require.

Yaw control: no longer optional

With no differential braking available, yaw control becomes essential.

Garmin would almost certainly require:

- a rudder servo,

- yaw-damper functionality,

- and full integration with approach, flare, and rollout logic.

This servo would serve three purposes:

- crosswind correction on final,

- alignment at touchdown,

- and directional control during the early rollout phase, while rudder and nosewheel steering remain effective.

Without this, Garmin would simply not offer Autoland on the airframe.

Configuration authority: flaps as commands, not suggestions

While the Sling already enforces flap protections through the avionics, Autoland would require positive authority over configuration.

In practice, this means:

- explicit flap commands from the Autoland logic,

- positive confirmation of flap position,

- and immediate re-planning if configuration changes fail.

From Garmin’s perspective, this is relatively low-risk. It’s largely a matter of software authority and feedback, not new actuators.

Autobraking: boring, symmetric, predictable

Garmin would not redesign the Sling’s brake system to be differential. Instead, they would add a single, symmetric autobrake actuator tied to the existing brake master cylinder.

The goals would be simple:

- smooth, ramped braking,

- conservative deceleration rates,

- immediate release on fault,

- and long runway assumptions.

The system would deliberately avoid aggressive braking or short-field heroics. Autoland’s job is not to stop quickly — it’s to stop safely.

The supervisor: separating authority from execution

Crucially, Garmin would not run Autoland logic entirely inside the G3X displays.

They would add a dedicated supervisory module, whose only job is to:

- monitor sensors and actuators,

- verify that commands produce expected results,

- and disengage or re-plan if the airplane’s behavior diverges from physical reality.

The dual G3X displays would act as:

- data providers,

- human interfaces,

- and control executors.

The supervisor would be the referee.

This separation of authority is what allows Garmin to ship Autoland with confidence.

Human interface and expectations

Finally, Garmin would design for fear.

The system would include:

- a clearly identifiable Autoland activation button,

- unmistakable annunciation when Autoland is active,

- spoken instructions via the audio panel,

- and clear guidance after stopping.

Nothing would be subtle. Ambiguity is the enemy.

Thread Two: A Emergency Landing Assist for the Rest of Us

Seen this way, the minimal Autoland concept starts to look less like a hack and more like a deliberate product tier — one that a company like Garmin could plausibly offer without turning every airplane into a Vision Jet.

This isn’t “Autoland Lite.” It’s a different product, with different outcomes and a deliberately different safety envelope.

A powered Smart Glide

At its core, Emergency Landing Assist is Smart Glide extended forward in time.

Instead of answering “where can I glide?”, it answers:

“where can I land safely, with power available?”

The technology required to do this already exists:

- moving maps and terrain databases,

- runway characteristics,

- weather and winds,

- navigator access to instrument approaches,

- aircraft performance models.

What’s missing isn’t data or sensors — it’s a mode that explicitly optimizes for landing rather than reachability. That’s a software decision, not a hardware breakthrough.

From FAF to pavement: we already trust the machine

Modern Garmin autopilots already fly coupled precision approaches down to 200 feet with remarkable consistency. In an emergency context, extending that guidance all the way to touchdown is not a technical leap — it’s a policy decision.

Emergency Landing Assist doesn’t need to promise smoothness. It needs to promise:

- stabilized path,

- correct alignment,

- predictable behavior.

The airplane already knows how to do most of that.

Power management: assist, automate lightly, or automate fully

Power management is where Emergency Landing Assist most clearly departs from a full OEM Autoland — and where flexibility matters more than elegance.

A Emergency Landing Assist does not require a sophisticated, continuously optimizing autothrottle. What it requires is the ability to remove thrust at the right time, predictably, and to avoid gross energy mismanagement on final. There are several viable ways to achieve that, and they don’t need to be mutually exclusive.

At the most basic level, power can remain a shared responsibility. The system can provide explicit, unambiguous audio instructions to the passenger — when to reduce power, when to pull it to idle — while the autopilot manages attitude, alignment, and descent. This alone removes the most cognitively demanding parts of the landing while leaving the human with a task that is binary and achievable under stress.

A step up from that is the addition of a simple throttle servo. Not a full autothrottle, but a deliberately constrained actuator whose job is limited to gross power changes: setting a conservative approach power and pulling the throttle to idle at a defined height above ground. With a constant-speed propeller and FADEC-managed engine, this level of control is often sufficient. The system doesn’t need to finesse thrust — it just needs to be decisive.

Crucially, such a servo does not have to eliminate manual control. It can be backdrivable, fail-safe, and overrideable, preserving the experimental ethos while materially reducing workload at the most critical moment. In normal operations, it does nothing. In an emergency, it becomes a very blunt but very effective tool.

At the high end, a more capable throttle actuator could support tighter airspeed control on final. But Emergency Landing Assist doesn’t depend on that. Its promise is not optimization; it’s predictability.

The key insight is that power does not need to be perfect to be safe. It needs to be removed at the right time, and it needs to stay out of the way while the airplane flies a stable path to pavement. A simple servo — or even clear instructions — can accomplish that.

One real hardware addition: yaw control

There is one piece that can’t be hand-waved away: yaw.

To land and stay aligned on a runway without pilot feet on the pedals, the airplane needs a rudder servo. Fortunately, this is a solved problem:

- the autopilot already supports yaw,

- the airframe already accommodates it,

- adding the servo is straightforward.

This is not speculative technology. It’s a practical upgrade.

Flare and rollout: safe, not pretty

With radar altitude available, the flare can be simple and deterministic. Touchdown may be firm. That’s acceptable.

Runway alignment is managed through yaw control. Braking can be delegated to the passenger once speeds are low, or handled minimally to avoid excursions.

Emergency Landing Assist assumes:

- long runways,

- conservative crosswind limits,

- and no heroics.

That’s not a weakness — it’s the entire design strategy.

Why Garmin Might — and Might Not — Do This

At first glance, a Emergency Landing Assist feels like something Garmin should build. It aligns neatly with the company’s long-standing philosophy: incremental safety gains, software-led capability, and deep integration across navigation, automation, and human interface. And yet, the very things that make Emergency Landing Assist attractive also explain why Garmin might hesitate.

Why Garmin might not do it

The most obvious reason is liability.

Garmin’s full Emergency Autoland makes a very strong promise: when activated within its defined envelope, the system will land the airplane safely without human involvement. That promise is narrow, conservative, and defensible. A Emergency Landing Assist, by contrast, would be explicitly imperfect. It would tolerate passenger involvement. It would accept firm landings, long rollouts, and strict limitations. It would aim for survivability, not polish.

From a product-liability perspective, that ambiguity is dangerous.

An imperfect system that saves lives most of the time still creates uncomfortable questions in the remaining cases. If the airplane lands but veers off the runway, was that a success or a failure? If a passenger misunderstands an instruction, is that a system defect or human error? The moment a system asks a non-pilot to do anything, the boundary of responsibility becomes blurred — and blurred boundaries are where litigation thrives.

There’s also the risk of expectation mismatch. Even with careful marketing, many users would mentally upgrade Emergency Landing Assist into “real Autoland.” When outcomes fall short of that imagined standard, disappointment turns into blame. For a company that has spent decades building trust through conservatism, that’s not a trivial risk.

Finally, there’s the question of brand discipline. Garmin Autoland today is deliberately rare, expensive, and tightly controlled. Introducing a visibly constrained version could dilute the clarity of what “Autoland” means in the market. From a branding standpoint, sometimes it’s safer to do fewer things exceptionally well than many things approximately.

Why Garmin might do it anyway

And yet, there are equally strong reasons why Garmin might decide the risk is worth taking.

The first is vertical integration. Garmin’s competitive advantage isn’t any single feature — it’s the way navigation, automation, sensing, audio, and human interface all reinforce each other. A Emergency Landing Assist would deepen that integration further. It would turn the Garmin stack into not just a flight system, but an outcome-management system — one that explicitly addresses the worst-case scenario in single-pilot GA.

The second is fleet impact. Full Autoland will always be limited to a relatively small number of high-end aircraft. A Emergency Landing Assist, by contrast, could apply to a vastly larger installed base: experimentals, light GA, owner-flown aircraft that already carry much of the required hardware. Even a modest reduction in fatal outcomes across that fleet would represent an outsized safety contribution.

There’s also precedent. Garmin has repeatedly introduced safety features that initially felt uncomfortable or intrusive — ESP, envelope protection, Smart Glide — and then watched them become normalized. Each time, the company chose to define clear limits, accept some residual risk, and trust that the net effect would be positive. Emergency Landing Assist follows that same pattern, just one step further down the decision chain.

Finally, there’s a quieter but powerful incentive: stickiness. The more safety-critical capability lives inside a vertically integrated Garmin ecosystem, the harder it becomes for owners to imagine flying without it. Emergency Landing Assist wouldn’t just be a feature; it would be another reason to stay within the Garmin world when building, upgrading, or buying the next airplane.

The tension that defines the decision

In the end, the question isn’t whether Emergency Landing Assist is technically feasible. It clearly is.

The real question is whether Garmin is willing to ship a system whose success criteria are intentionally modest — a system that promises not perfection, but survival. That’s a harder promise to word, defend, and stand behind. It’s also the kind of promise that, if handled carefully, could reshape safety expectations across a much larger part of general aviation.

That tension — between liability and impact, clarity and reach — is likely the real reason Emergency Landing Assist doesn’t exist yet.

Bringing It Together: Three Outcomes, Not Two

At this point, the shape of the problem — and the opportunity — becomes much clearer.

Today, in most single-pilot GA aircraft, serious pilot incapacitation tends to collapse into a narrow set of outcomes. Either the pilot recovers enough to land, or the automation never takes the final step needed to save the flight. The airplane may remain stable for a while, but stability alone does not get you onto a runway.

Full Garmin Autoland breaks that pattern decisively. It removes the human from the loop entirely and replaces them with a tightly integrated, responsibility-owning system that can choose a runway, fly the approach, land, stop, and manage the aftermath. It is comprehensive, conservative, and expensive — because it has to be. When Garmin ships Autoland, it is making a promise about outcomes, not just capabilities.

Emergency Landing Assist sits deliberately between those two extremes.

It does not attempt to eliminate the human. It does not promise perfection. Instead, it introduces a third outcome: the pilot does not recover, but the airplane still lands under control.

That difference matters more than it first appears.

In the Sling TSi context, the gap between “today” and “Emergency Landing Assist” is surprisingly small. Most of the hard problems are already solved. The airplane already knows how to stay upright, respect its envelope, navigate precisely, and fly a stabilized approach. It already has the data needed to select a suitable runway. What’s missing is intent and authority — the decision to extend existing automation one step further, and the small amount of hardware needed to support that decision.

Critically, Emergency Landing Assist does not require solving every problem at once. It tolerates shared responsibility. It accepts passenger involvement for tasks that are simple and low-risk. It allows for firm landings, long rollouts, and conservative envelopes. Its success criteria are intentionally modest: not death, not perfection.

Seen this way, Emergency Landing Assist doesn’t compete with full Autoland. It complements it. Full Autoland is the right answer when you want certainty regardless of who is onboard. Emergency Landing Assist is the right answer when you want to dramatically improve survivability for a much larger portion of the fleet — aircraft that will never carry the cost, weight, or integration burden of a Vision Jet–class system.

This is also where the historical parallels come back into focus. ESP did not replace pilots; it quietly prevented loss of control. Smart Glide did not eliminate engine failures; it gave pilots time and options. Both features redefined what “good enough” safety looked like before becoming widely accepted.

Emergency Landing Assist follows that same pattern. It doesn’t ask whether an airplane can land itself perfectly. It asks whether, on the worst day imaginable, we can do better than hoping the pilot wakes up in time.

For aircraft like the Sling TSi — modern, capable, and already deeply automated — the answer increasingly looks like yes.

Leave a comment